Product details

Franck Bridge

1. Sonata

Benjamin Britten

Suite opus 6

2.Introduction - March

3.Moto perpetuo

4.Lullaby

5.Waltz

Alan Rawsthorne

Sonata (Dedicated to Joseph Szigeti)

6. Adagio Allegro non troppo

7. Allegretto

8. Toccata (allegro di bravura)

9. Epilogue (adagio rapsodico)

Recorded at the Théâtre de Poissy

November 2003

AR RE-SE 2003-6

English impressions

In the history of English music, Frank Bridge (1879-1941) stands out as a creator who is as discreet as he is fascinating. Born in Brighton, Bridge was introduced to music by his violinist father. Logically, it was around the violin that the musical education of a child was organised, and it is worth noting that he was soon to be confronted with the demands of collective practice by participating in the light music groups that his father regularly directed.

A traditional path for a talented young English musician, Bridge studied at the Royal College of Music between 1896 and 1903. Between violin and viola, he showed a clear preference for the latter - and became a first-rate performer! He also worked on the piano. His vocation as a composer was also confirmed and he acquired a solid craft with Sir Charles Villiers Stanford.

Once he had completed his studies at the Royal College, the artist's life was divided between creating and playing music. The need for the young musician to support himself certainly explains in part why Bridge exploited his talents as an instrumentalist. There is no doubt, however, that he derived great satisfaction from his participation in various London orchestras and, even more so, from his regular participation in chamber music. A keen string quartet player, Bridge worked with three groups from 1903, in particular the English String Quartet, of which he was violist until the early 1920s.

The musician's curiosity also led him to conducting. As assistant conductor of the young New Symphony Orchestra and of the Orchestra of London's Savoy Theatre, Bridge learned a great deal there too. His baton earned him a fine reputation which earned him the opportunity to replace a Beecham at Covent Garden or a Henry Wood during the Prom's and allowed the composer to perform his works in England and the United States (where he made a major tour in 1923).

Symphonic music occupies a significant place in Bridge's output, and works such as the suite The Sea (1911) were very well received. Nevertheless, it is in chamber music that the composer finds his most natural field of expression, the one best suited to satisfying a secret and demanding nature - Britten witnessed this!

Bridge's first major achievements in this field date from the mid-1900s and allow us to follow closely the development of his language until 1938.

The First World War was a real turning point in the development of a person deeply affected by the spectacle of human slaughter, which reinforced his pacifist convictions. This trauma, added to the regret of not having been able to taste the joys of fatherhood (1), contributed to the transition from the lyrical and immediately accessible style - a bit Faurean, one might say - of his early work to a complex language tinged with bitterness. Under the influence of Scriabin and the Viennese, Bridge allowed himself more and more liberties with the tonal system: atonality, polytonality and bitonality are recurrent terms when one looks at his work from the early 1920s onwards. "But," Harry Halbreich pertinently remarks on the subject, "the effect on the listener is rather that of a prismatic refraction of harmony, giving rise to very complex aggregates." Dedicated to the memory of a fallen friend, Ernest Bristow Farrar, the vast Piano Sonata (1921-1924) provides the first illustration of this radical change of direction. Completed at the cost of a long and absorbing workload, this score was followed by a rapid return to chamber music with the 3rd String Quartet (1925-1927). The latter opened a fertile period which, passing through the Rhapsody Trio (1928) and the superb 2nd Piano Trio (1929), led in 1932 to the Sonata for Violin and Piano H. 183.

The dedication of the work to Mrs Elisabeth Sprague Coolige expresses the composer's gratitude to a wealthy American patron of the arts (2) whom he met in 1922, as he presented her with one of his highest achievements. A testament to the master's great maturity, the Sonata H. 183 is distinguished by its monolithic character and is composed in four episodes. An Allegro energico introduction leads with élan and expression to the Allegro molto moderato, whose complexity of feeling is immediately apparent. Whether in terms of dynamics or tempo, a taste for nuance characterises the mysterious and carnal dialogue between the two instruments in a development of rare nobility. A bar of silence, and the piano begins the second movement Andante molto moderato, soon joined by a questioning violin. Whether in the extreme sections, full of restless pain, or in the middle section, full of restrained fever, one cannot help but be struck by a sense of balance that continuously combines lyricism and transparency. A long hold by the violin and the Scherzo vivo e capriccioso emerges! Mobility of speech and virtuosity are certainly the order of the day in this movement, but it is nevertheless with a feeling of bitterness, of impossible joy that we leave it, while a brief lento transition leads to the Allegro molto moderato finale. A tempo identical to that of the first movement? Bridge is in fact reusing elements already exploited at the beginning of the work. They simply gain in dramatic intensity and the success of this reminiscent movement contributes greatly to the overall coherence of the sonata.

Frank Frank Bridge and Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) together in one programme? What could be more natural when one remembers the decisive influence that the former had on the future author of Peter Grimes, both from a musical and a human point of view! Had he not been a conductor, Bridge might never have become Britten's teacher... In 1924, Britten had the opportunity to hear Bridge conduct his symphonic suite The Sea at the Norwich Festival. The experience proved decisive for a young man whose desire to dedicate himself to composing grew day by day! Through the violist Audrey Alston, Britten came into contact with Bridge, but it was some time before the lessons began, as it was not until 1928 that a crucial period in the young artist's development began. Bridge had already taught violin and viola, but never composition: his choice was a wise one, to say the least!

Self-taught, Britten had already tried his hand at composing, but in truth he still had a lot to learn when he began working with Bridge. What demands were suddenly made on him! This pedagogy was a real test for a budding composer, but he was building irreplaceable tools!

Britten summed up the essence of a rigorous pedagogy, the positive effects of which did not take long to manifest themselves, since the Four French Songs were published in the summer of 1928. 1930 marked the completion of the lessons with Bridge and Britten's entry into the Royal College of Music, whose academic atmosphere was not to the young man's liking. The wonderful relationship with his first teacher was only a memory and he hardly took to John Ireland's teaching... Britten continued to develop his art, however: successes such as the Sinfonietta op. 1, the Phantasy Quartet op. 2 and the Simple Symphony op. 4 testify to this - the latter, dated 1934, corresponding to the end of his studies at the Royal College. The composer's name was soon circulating on the continent. In March 1934, Britten gave a performance of his Opus 2 in Florence, and in April 1936 he was at the keyboard in Barcelona with the violinist Antonio Brosa for the premiere of the Suite for Violin and Piano Op. 6.

One cannot resist this youthful composition of brilliance, wit, humour and delicious harmonic ambiguities! A short Andante maestoso introduction precedes the first March episode (Allegro maestoso) with its bouncy and slightly mocking freshness. The Moto perpetuo (Allegro molto e con fuoco) takes the listener on a virtuoso ride, always punctuated by a note of surprise. With a violin con sordina, the third piece, Lullaby (Lento tranquillo), unfolds a moonlit lullaby, irresistible in its tenderness and lyricism, before the concluding Waltz (Vivace e rubato) makes numerous references to the three-beat dance in an elegantly parodic fashion.

After the work of a twenty-two-year-old musician, Alan Rawsthorne's (1905-1971) Sonata for Violin and Piano - like Bridge's - presents us with a work of great maturity by its composer. He is one of the most unknown figures in English music on this side of the Channel and has had an atypical career to say the least. After a long search for his path - and even considering becoming a dentist or an architect! - Rawsthorne only began to study music seriously at the age of nineteen. But with great zeal! In 1925 he entered the Royal College of Music, where he worked with the pianist Frank Merrick and the cellist Carl Fuchs. Very attracted to the piano, he went to the continent to study with a disciple of Ferruccio Busoni: Egon Petri. In addition to his work as a teacher, Rawsthorne made a name for himself as a composer in the 1930s. In 1938, his Theme and Variations for two violins was a great success, amplified the following year by the premiere of the Symphonic Studies for Orchestra and the Piano Concerto No. 1. Generally speaking, the concerto field was a success for the musician, as attested by the Violin Concertos Nos. 1 (1948) and 2 (1956) and the Piano Concerto No. 2 - premiered by Clifford Curzon in 1951, shortly before making a recording with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent.

The interest shown in Rawsthorne's output by leading performers is commendable. In addition to Curzon, John Ogdon inspired the composition of the vast Ballade for piano and orchestra (1967) and gave its first performance. Gérard Gefen (3) summed up Rawsthorne's situation well when he remarked that 'while composers of the British avant-garde do not always manage to conceal their ties with tradition, Alan Rawsthorne's case is exactly the opposite. In the genres in which he chooses to compose and the general principles of his writing, he belongs to the classical tradition. In harmonic matters, the composer is more inclined to ambiguity than to rupture and his music has a particular colour. This, together with the "inactual" nature of his ties to the past in the middle of the 20th century, contributes to the very endearing character of an output in which there is still much to discover. Rawsthorne's attraction to the orchestral world did not lead him to neglect chamber music. In addition to three string quartets (1940, 1954 and 1965), he wrote a Clarinet Quartet (1948), a Quintet for piano and winds (1963), a Sonata for cello and piano (1949) and several works for violin and piano. Of these, the Sonata, composed in 1959 and dedicated to Joseph Szigeti, undoubtedly dominates. In four parts, it begins with an Allegro non troppo remarkable for its purity and modesty, which has the originality of being framed by a short Adagio section of an openly dramatic character. The second movement Allegretto, with the violin con sordina, develops in a climate of questioning tenderness and closes pp morendo. In total contrast to the preceding, the Toccata (Allegro di bravura) engages in a breathless, virtuosic discourse, but also allows for moments of lyricism and astonishment before the Epilogue (Adagio rapsodico) closes the work with freedom, poetry and dreaminess.

Alain Cochard

(1) Ether, his wife since 1908, was unable to give him children.

(2) Bridge was largely indebted to him for the tour of the United States in 1923.

(3) Histoire de la Musique anglaise (Ed. Fayard).

The press is talking about it!

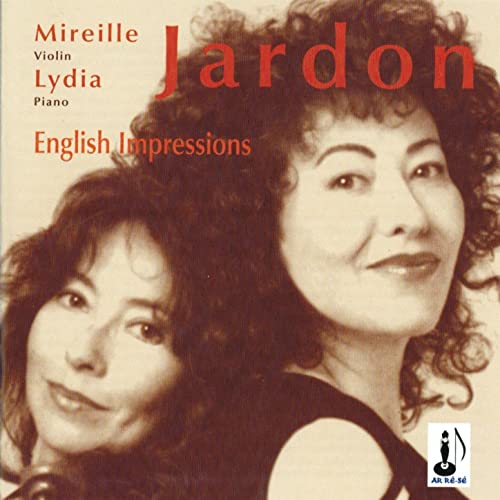

"Initiator, in 2001, and artistic director of the first "Rencontres de musiciennes" in Ouessant ("l'île aux femmes"), after having launched a summer academy there in 1993 for professionals and amateurs, Lydia Jardon is a passionate and activist artist; she has even created her own record label AR RÉ-SÉ ("celles-là" in Breton) On the piano too, she is an impressive performer. We find her strength of conviction on this disc recorded with Mireille Jardon on the violin (who belongs to the European Community Orchestra and has joined the Radio-France Philharmonic Orchestra). No beaten track for this duo, one can imagine. So here they are, taking on pages from across the Channel with sonatas by Frank Bridge and Alan Rawsthorne and a Suite by Benjamin Britten. With a very assertive conviction, a catchy ardour.

Dernières nouvelles d'Alsace, May 7th 2004

![]()

"Jardons in the English style. The pianist Lydia Jardon has made a name for herself with her serene virtuosity, not least thanks to the numerous recordings she has made for her own label. With her lesser-known sister Mireille, she forms a good violin-piano duo, which caught our attention above all by an original and very English programme. A suite by Benjamin Britten with very descriptive atmospheres, a sonata by his master Frank Bridge, marked by post-romantic impulses, and another signed by Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971), well forgotten on this side of the Channel but endowed with a classical and perfumed writing of the most seductive kind. In any case, by going off the beaten track, the Jardon sisters show that they are perfectly at home in the British mists and light shadows, while deploying, one with vibrating lines on the bow, the other with a solid piano tapestry. To be discovered."

La Croix, June 2004, Jean-Luc Macia

![]()

"This is a rare and unexpected programme from French artists. From the very first bars of Bridge's Sonata, the listener understands that he is not dealing with a lukewarm disc. Bridge composed his only Sonata for violin and piano in 1932, at the height of his maturity and after the one for solo piano which had marked a turning point in his writing. In a single movement, this sonata is boldly modern in the England of the time and has not aged a bit. Dedicated to the great American patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, who commissioned several of Bridge's works (and Stravinsky's 'Dumborton Oaks' Concerto), it stands out for its virtuoso style. A pupil of Bridge, Britten composed his Suite in 1934-35 in Vienna. It provides a further demonstration, after the Sinfonietta op. 1 and the Simple Symphony op. 4, of the young composer's mastery of writing for string instruments. The varied moods, with a nod to The Soldier's Tale, express the young composer's exuberance and confidence in his gifts. Alan Rawsthorne, the least known of the three composers, has tried his hand at almost every genre except opera. His violin sonata (1959) is dedicated to Josef Szigeti. In four movements, it displays the composer's usual elegance. In perfect harmony, the Jardon sisters offer us an irresistible disc... ".

Music World, April 2004, John Tyler Tuttle

![]()

"Twin sisters or Siamese sisters? One wonders, so much so that Mireille and Lydia Jardon seem to merge into one musician. For this foray across the Channel, turning their backs on Vaughan Williams's "cow-dung" pastoralism, they have chosen three allusive works that are difficult to access, whose informal implications are as important as the text. The clarity and naturalness of their approach give these pages a transparency that will make them obvious to the most resistant. The Bridge Sonata is one of the peaks of his last, 'modernist' period; the impressionist heritage is interwoven with expressionist chromatic tendencies. The performers know how to reconcile these antagonisms and achieve a purity of style and a balance of construction ideally suited to the composer's intentions. Lydia delivers the crystalline sonorities of the piano, decanted in the treble, with a restraint that accentuates their mystery and unreal poetry. The Scherzo is a moment of perilous and unbound virtuosity, whose control preserves the dreamlike quality. In contrast to the slightly outré expressionism of Lorraine McAslan and John Blakely (Continuum, 1991), the Jardon sisters play the classicism card. Another conception, well defended, of the refinement and elegance of the last Bridge. More 'light', Britten's Suite is dazzlingly witty, lively, and facetiously witty. Incisive contrasts, apropos accelerations, and delicate timbre are the prize of this sophisticated reading. Rawthorne calls for more reservations: at least the perfect synchronisation does justice to the somewhat formal linear dialogue of the voices. Breaking intelligently with the routine, the sisters dispense a brio, a "chic" and a poetry that will rally the most obstinate enemies of perfidious Albion.

Diapason, May 2004, Michel Fleury

![]()

"We have long known the remarkable pianist that Lydia Jardon has always been. Here she is again, this time with her own sister (a violinist) in a fascinating programme, excellently conceived and performed, happily coupling the too rare Sonata for violin and piano by Bridge (1879-1941) with the no less unknown - and no less interesting - Suite opus 6 by Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), and then Alan Rawsthorne's Sonata (1905-1971), dedicated to the great violinist Joseph Szigeti. Through the depth of sound of two performers who always seem to be singing with one and the same voice, they are not sisters for nothing, through the (sometimes painful) depth of a playing of a skin-deep and uncompromising expressivity, through the elegance and the curvature of the phrasing, but also through the personal and emotional investment - considerable - of the two musicians, this rare disc must be considered as an absolute reference in the field and must be known by all lovers of great English music of the 20th century: Indeed, few duets have been able to express to such a degree the embracing emotions of the Bridge Sonata - to name but one. Far, far from the academic and absolutely "uptight" coldness that too many chamber musicians feel obliged to adopt when faced with scores that are much more emotional (or even immodest) than is generally admitted - could it be because Bridge was English - the Jardon sisters go straight to the heart and soul of these pages, passionately delving into every detail, every corner. Moreover, the coherence of the coupling bringing together three English composers of the same period, certainly different, but with a common sensitivity and using a language that is not very far from each other, only increases the interest of a first-rate disc.

Piano Magazine, March-April 2005, Robert Harmon