Détails produit

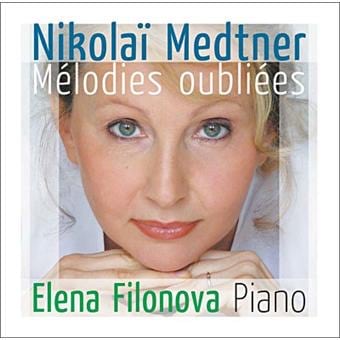

Mélodies oubliées

Vergessene Weisen opus 38

1.Danza festiva

2.Canzona fluviala

Vergessene Weisen opus 40

3.Danza col canto

4.Danza jubilosa

Vergessene Weisen opus 38

5.Canzona serenata

Vergessene Weisen opus 39

6.Meditazione

7. Romanza

8.Primavera

9.Canzona matinata

10.Sonata tragica

Arabesques

Drei Arabesken opus 7

11.Ein Idyll

12.Tragoedie-Fragment n°1

13.Tragoedie-Fragment n°2

Production, Ingénieur du son : Lubov Doronina.

Mastering : Pavel Lavrenenkov.

Enregistré à Moscou, Mars 2004

AR RE-SE 2005-9

Résumé

Mélodies oubliées, mélodies retrouvées…

« J’ai toujours cru que l’Art, comme la nature, est l’œuvre du Créateur. Mes principes ? Je tâche de faire croître dûment la semence qui vient d’en Haut, sans inventer de nouvelles lois. »

Nikolaï Medtner (1880-1951)

L’histoire de la réception de l’œuvre de Medtner est celle d’un malentendu. Trop passionnée pour les tenants de l’avant-garde, trop complexe pour les foules rompues aux élans enfiévrés d’un Rachmaninov, la musique de Medtner n’aura pas vraiment su gagner les faveurs du grand nombre. La comparaison avec Rachmaninov n’est pas hors de propos, mais elle est perfide : aujourd’hui encore, Medtner souffre de se voir évalué à l’aune de celui qui fut l’un de ses plus fervents partisans. Ce qui distingue artistiquement les deux hommes est pourtant plus déterminant que ce qui les réunit.

Le piano de Medtner est bien sûr romantique, virtuose et lyrique ; mais rien n’y cède à la facilité, car l’écriture du clavier est tenue d’une main de fer. Les structures des œuvres sont souvent épiques, au risque de perdre leur auditeur. Elles sont pourtant fermement maîtrisées : les flots tumultueux de l’inspiration sont endigués par une conduite des événements sans faiblesse. Medtner le paradoxal est un équilibriste évoluant sur un fil fragile, tendu d’un côté par une volonté ardente d’expressivité, de l’autre par un souci de rigueur et d’ascèse.

L’existence de Medtner ? On peut la brosser à grands traits : naissance en 1880, études au Conservatoire de Moscou. Une vie dévouée à la composition, mais passée sur les estrades. Et puis, les exils : le premier en 1921 vers Berlin, pour fuir la Russie bolchevique. Mais l’Allemagne n’a que faire de ce musicien qu’elle décrète trop conservateur sans le comprendre vraiment. Un deuxième exil à Paris, peu après. Où malgré l’appui d’un cercle de fidèles, la vie reste difficile, et décevante. Des tournées à travers le monde. Un dernier exil en 1935, vers Londres. Le succès est enfin au rendez-vous, mais la guerre approche, et finit par en briser l’élan. Ultime apparition publique au Royal Albert Hall en février 1944. L’aide inattendue du Maharajah de Mysore permet à Medtner d’enregistrer pour His Master’s Voice. Avant qu’il ne disparaisse en 1951. Si loin de la Russie, si loin des siens.

L’homme Medtner apprendra pourtant bien peu du compositeur, moins encore de l’œuvre. Sa musique ne doit rien aux circonstances, elle est le secret révélé d’une âme dont les préoccupations sont fondamentalement musicales. Medtner se donne des limites, pour viser plus juste : la musique pure sera son terrain d’élection, notamment à travers la sonate, héritée de Beethoven, le modèle vénéré. Medtner affirmait être né un siècle trop tard, et jamais d’ailleurs il n’adhéra au nationalisme musical post-romantique de ses « Cinq » aînés Russes.

Ce qui n’empêche pas la substance de ses œuvres d’être particulièrement élaborée. Dans les sonates ou les pièces brèves, le développement procède d’une transformation perpétuelle d’éléments de base, souvent un thème unique. La Sonata tragica (Sonate tragique, n°11) en est l’exemple parfait. Les accords frappés à l’ouverture donnent à cette œuvre d’un seul tenant l’élan du souffle unique qui la parcourra tout au long. L’imagination et le métier consommé de Medtner lui permettent de présenter le seul thème sous un nombre infini de visages. Et c’est presque comme autant de scènes d’opéras qu’il faudrait entendre le déroulement des différents épisodes, tant la marche agogique d’ensemble paraît être d’essence dramatique. La dernière percée du développement est exemplaire (7’09), longue montée en tension qui finit par culminer dans la réexposition même des accords initiaux de l’œuvre (7’38). Preuve qu’une forme d’origine classique n’empêche aucunement la pensée rhapsodique de jaillir dans l’instant. Une stupéfiante coda (10’29) achève de liquider les derniers linéaments du thème. Le mouvement s’abîme dans les harmonies mêmes qui l’avaient ouvert.

Medtner affectionnait particulièrement d’interpréter en concert cette œuvre organique. Mais il ne manquait jamais de la faire précéder de la Canzona matinata. Cette « Chanson du matin » présente deux idées tranchées dans leurs caractères, l’une toute de grâce et d’insouciance, l’autre plus mélancolique et presque inquiète, qui préfigure peut-être les tourments de la sonate à suivre. À vrai dire, les deux œuvres partagent secrètement une partie de leur thématique, procédé fréquent chez le compositeur.

Mais revenons au début de cet opus 39. La Meditazione (Méditation) qui l’ouvre est l’une des plus étranges inventions de Medtner. Une introduction « quasi cadenza » fait surgir du néant un monde angoissé, aux couleurs scriabiniennes (0’40). Le vrai thème de la pièce apparaît (1’25), mélodie désarticulée et condamnée à ne revenir qu’à elle-même. La musique finit par échapper à sa propre inertie, et s’achève sur une résolution majeure apaisée. La Romanza reprend le thème de la Meditazione pour l’exploiter jusqu’à l’obsession. Curieuse « Romance » en vérité, qui, sous des allures de valse mi-mondaine mi-diabolique, ne promet d’autre salut que la répétition méphitique d’un fragment rêche et résolument indomptable. L’impatiente Primavera (Printemps) vient apporter un peu de lumière à l’opus 39. Entre les deux diptyques plutôt ténébreux qui l’entourent, elle offre un intermède joyeux et ensoleillé.

Composés en 1919 et 1920, ces Vergessene Weisen (Mélodies oubliées, opus 38, 39, et 40) furent imaginés dès 1916. Il est fort probable que Medtner se soit inspiré d’un texte de l’écrivain russe Lermontov (1814-1841). Dans son poème L’Ange, Lermontov raconte que chaque nouvel enfant, porté par l’ange qui le mène du ciel à la terre lors de sa naissance, entend une mystérieuse musique : son existence ne sera qu’une longue quête pour en retrouver les célestes échos. En ce récit poétique, Medtner vit sans doute la métaphore de l’inspiration artistique, lui qui ne cessait de s’étonner des idées musicales qui frappaient son imagination. Ces pièces placent également l’invention medtnérienne sous le sceau singulier de la réminiscence : réminiscence (ou renaissance) de ces mélodies originellement « oubliées », réminiscences (ou correspondances) thématiques reliant entre eux différents morceaux d’un même opus, réminiscences (et métamorphoses) perpétuelles d’un unique matériau au sein d’une même pièce.

Deux pièces de l’opus 38 sont présentées sur cet enregistrement. La troisième, Danza festiva (Danse de fête) peut évoquer une fête de village, avec ses scènes festives et de liesse populaire. Cette valse légère débute par une rustique sonnerie de cloches : des accords alternés aux deux mains, que l’on retrouve, minorisés et transposés d’un ton, à l’ouverture de la pièce suivante, Canzona fluviala (Chanson de la rivière). Moins que jamais dans ce morceau gracieux le titre aura recouvert la réalité du contenu musical. Remarquons plutôt la présence de titres italiens et faisant référence à une vocalité ou à une gestualité (« Danse de fête », « Chanson de la rivière », « Romance », « Chanson du matin », « La danse avec le chant », « La danse joyeuse ») : on peut voir en cela une volonté d’accorder la primeur à un certain lyrisme, par le retour à une naturalité toute latine du corps et du chant. Ce que tendrait à prouver la Canzona serenata (Chanson sérénade) sixième pièce de l’opus 38, un pur joyau de simplicité et d’émotion. Le thème liminaire instaure un balancement mélancolique, soutenu par des harmonies particulièrement subtiles. Un deuxième élément thématique l’interrompt (0’37) ; frémissant passage chromatique à la basse (0’51), le discours se fait plus fervent (1’12), puis s’apaise. Soudainement, cette « sérénade » s’inquiète et s’anime de miroitements plus virtuoses (2’00). L’élément -secondaire reprend à nouveau ses droits (2’32) et son ton passionné (2’50). S’immisçant subrepticement dans la texture redevenue immatérielle, le balancement du départ fait son retour (3’20), épaissi d’un nouveau chant intérieur, puis s’éteint rapidement.

L’opus 40 des Mélodies oubliées est constitué de six danses, dont les première et quatrième sont ici présentes. La Danza col canto (la Danse avec le chant) se montre fort riche dans la construction de ses épisodes puissamment caractérisés. L’introduction va s’échauffant, et pose une métrique originale à 5/8. De longues arabesques nostalgiques s’épanchent (0’33), avant que ne réapparaissent les éléments introductifs (1’44). La partie centrale contraste, en présentant d’abord une sorte de tarentelle (2’12), puis, sur de puissantes roulades arpégées, une mélodie turbulente et naïve à souhait (2’32). Retour du thème d’arabesque (3’15), qui fait place au chant éploré, puis finalement menaçant, de l’introduction. La Danza jubilosa (Danse joyeuse) combine toutes les qualités d’un scherzo et d’une toccata : joyeuse, alerte, ironique, et surtout parfaitement pianistique. C’est un kaléidoscope d’épisodes variés : main gauche en octaves staccatos parodiant la majesté d’une procession, sonneries de cuivres, rythmes déhanchés ou figurations motoristes à la main gauche, guirlandes volubiles à la main droite. Une réussite instrumentale qui ne galvaude nullement la joie qu’elle promet.

Les Drei Arabesken (Trois arabesques) de l’opus 7 (composées en 1904) montrent que Medtner trouva son style dès ses débuts. En dépit d’une écriture pianistique apparemment stabilisée, le rôle des deux mains est fluctuant dans Ein Idyll (Une idylle) : parfois les doubles-croches de la main droite accompagnent, parfois elles conduisent le discours. Le chromatisme s’insinue (0’41) jusqu’à s’agréger en un motif troublant (0’59 et 1’26). Apparemment moins ambitieuse que les autres pièces de l’opus, Ein Idyll est pourtant révélatrice d’une conception pianistique qui tendra à conférer peu à peu aux deux mains la même éloquence. Cela n’est pas encore le cas dans les deux Tragoedie-Fragmente (Fragments de tragédie) de l’opus 7 : le premier répète inlassablement une figure de triolets à laquelle seule la section centrale offre un semblant d’apaisement. Avant l’agonie finale, qui se consume définitivement en de sombres octaves. « Écrire seulement une œuvre comme celle-là, et l’on peut mourir », s’exclama Rachmaninov. Les arpèges de main gauche qui soutiennent le second des Tragoedie-Fragmente constituent une véritable dentelle sonore qui laisse apparaître ses propres contrechants. Mais la main droite impose un motif chromatique en guise de thème. Réitéré anxieusement, il apparaît parfois dans des configurations contrapuntiques particulièrement complexes. Un luxe que se permet le compositeur dans cette atmosphère d’urgence désespérée qui en appelle au lyrisme indompté de certaines Études de Chopin.

Epilogue

La mère de Medtner, qui voyait l’union de son fils avec Anna Mikhaïlovna d’un mauvais œil, disparaît en mars 1918. Le 21 juin 1919, Nikolaï épousera celle qu’il a rencontrée vingt-trois ans plus tôt. Les difficultés politiques les amènent à se réfugier à Bugry, en périphérie de Moscou. Isolé de la capitale, Medtner doit renoncer à son poste de professeur au Conservatoire. Dans des conditions matérielles particulièrement difficiles, il compose ses Mélodies oubliées. En novembre 1921, Nikolaï et Anna font le choix d’un exil incertain à Berlin. Les opus 38, 39, et 40, auront marqué la fin de la période russe. La suite, on le sait, ne sera qu’instabilité et désillusion. Si la carrière de Medtner en tant que pianiste n’est certes pas négligeable, il restera un compositeur marginal et mal reconnu. Un mauvais sens de la publicité et des options esthétiques jugées dépassées empêcheront l’artiste d’accéder à la reconnaissance que sans nul doute il méritait comme créateur. Medtner n’avait pas de mots assez durs pour l’avant-garde de son temps. Il s’était expliqué de son credo artistique dans un texte de 1935, Muza i moda (La Muse et la Mode), dans lequel il affirmait la nécessité de sauvegarder certaines fondations de l’expression musicale. Position rationnelle si l’on comprend que ses efforts ne portèrent pas sur la remise en cause d’un langage, mais au contraire sur la recherche d’une parfaite maîtrise de ses structures existantes.

Loin des révolutions qui secouent le monde musical de la première moitié du XXe siècle, Medtner vise un beau idéal et abstrait. Son écriture répugne pourtant à toute facilité : bien qu’il écrivît exclusivement pour son instrument (fût-ce en lui en adjoignant d’autres), ses œuvres sont incontestablement celles d’un compositeur avant d’être celles d’un pianiste. Il faut se réjouir à la perspective d’une si belle musique à découvrir.

Nicolas Southon

Nicolas Southon enseigne à l’Université de Musicologie de Tours. Dans le cadre du CNRS (IRPMF), il prépare une Thèse d’histoire sociale consacrée à l’émergence du chef d’orchestre au XIXe siècle. Il est titulaire des Prix d’Analyse, d’Esthétique, et d’Histoire de la Musique du Conservatoire national supérieur de musique de Paris. Il est également critique et journaliste dans des revues musicales spécialisées, et a été producteur sur France-Musique en 2005.

La presse en parle !

Le Monde de la musique, Décembre 2005, Jean Roy

« Issu d’une famille germano-balte, Nikolaï Medtner est une des personnalités les plus singulières de la musique russe. Sa vie se résume ainsi : des études au Conservatoire de Moscou, l’exil en Allemagne dès 1921, puis à Paris et à Londres, une carrière partagée entre les récitals de piano et la composition. Dans son livre sur la musique de piano, Guy Sacre a consacré plus de vingt pages à Medtner, qu’il situe ainsi : « Il se range tout naturellement clans le camp des Moscovites, lesquels, loin du nationalisme des Cinq, pratiquent un art cosmopolite : façon compliquée de dire qu’ils ont des modèles allemands. » L’influence de Brahms n’a pas empêché le compositeur d’être fidèle à son pays natal. Les Mélodies oubliées dont Elena Filonova a enregistré des extraits (l’Opus 39 étant toutefois complet) ont pour origine la lecture d’un poème de Lermontov, L’Ange. Dans les bras d’un ange, le petit enfant entend des mélodies célestes que, toute sa vie, il tentera de retrouver. L’ange de Medtner était assurément un ange russe… Le romantisme du musicien intervient dans son écriture pianistique virtuose, qui se rapprocherait de celle de Rachmaninov, son ami et admirateur, s’il ne s’y greffait, comme par un sentiment de révolte, des moments de rupture où le compositeur se retranche dans un univers sans complaisance. C’est là sa grandeur : être à la fois très moderne par ses audaces harmoniques, sa liberté rythmique, et romantique à sa manière, toute personnelle, par le caractère de « confession » que sa musique revêt souvent, lorsqu’il fait parler I' »ange russe ». Elève d’Emil Gilels, par qui elle a été initiée à l’oeuvre de Medtner, Elena Filonova, qui vit en France mais donne souvent des concerts en Russie, joue les Mélodies oubliées et les Arabesques avec une sonorité superbe, une compréhension en profondeur de ces pages et une force de conviction auxquelles on ne résiste pas. »

Classica-Répertoire, Février 2006, Michel Fleury

« Un programme intelligemment composé qui pourrait servir d’introduction au maître russe : des extraits des trois grands cycles inspirés par le poème de Lermontov L’Ange, texte donnant la clef de la conception que le musicien avait de l’inspiration artistique. L’existence de l’artiste ne serait à l’en croire qu’une longue quête pour retrouver l’écho des mélodies célestes entendues au moment de la naissance de chaque être lorsqu’il est convoyé par un ange du ciel à la terre. Danses festives, élégiaques ou fantastiques, chants de sérénité ou de jubilation, ces Motifs oubliés (1920) témoignent d’une rare perfection formelle. Le beau contrepoint, la complexité du rythme et la plénitude harmonique se coulent dans une écriture pianistique dont la plasticité s’apparente au meilleur de Schumann ou de Chopin. Le jeu d’Elena Filonova possède une remarquable clarté qui autorise des tempos assez vifs sans préjudice pour la riche polyphonie medtnérienne. C’est une pianiste élégante, dont la ligne racée pourrait se comparer à celle de la grande pianiste américaine Constance Keene dans les Préludes de Rachmaninov (Philips). La profusion un peu improvisée de la musique y gagne en cohésion, et cette approche apollinienne souligne l’héritage beethovénien implicite du compositeur russe. (…) Réussite globale d’un disque dont le goût presque parfait et la haute tenue constituent d’appréciables atouts. Et l’on se félicitera de l’intérêt porté à Medtner par de nouvelles générations de pianistes à un musicien si longtemps brocardé sous prétexte de « romantisme attardé ». »