Details

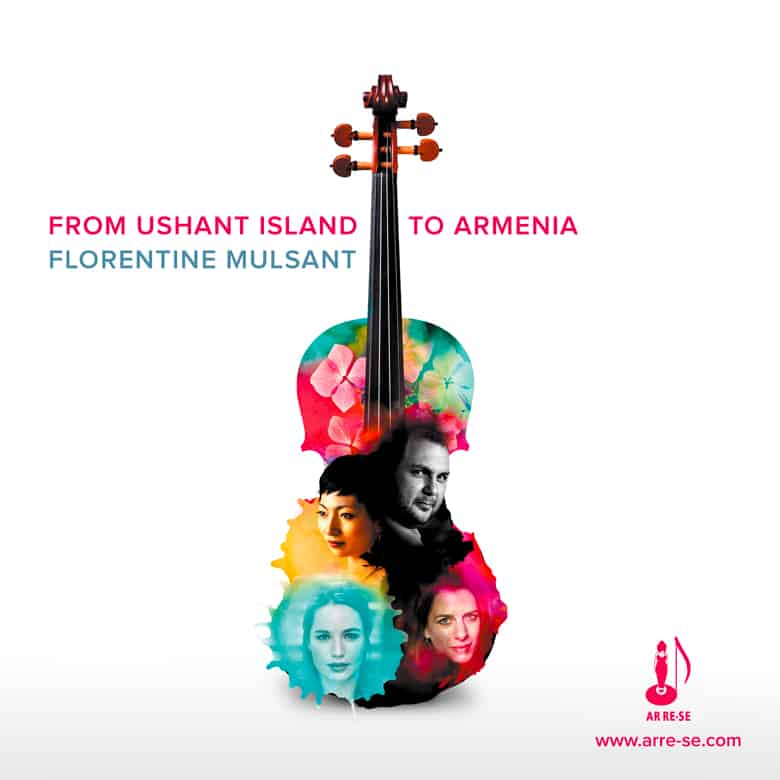

Florentine Mulsant , Composer

Isabelle Duval, flute

Asako Yoshida, piano

Lise Berthaud, viola

Stéphanie Carne, clarinet

Tchaika Trio: Elena Khabarova, violin / Sofiya Shapiro, cello

Alexandra Matvievskaya, piano

Ingrid Schoenlaub, cello

The National Chamber Orchestra of Armenia, conducted by Vahan Mardirossian

VARIATIONS FOR FLUTE AND PIANO OP. 11

Isabelle Duval, flute

Asako Yoshida, piano

VOCALISE FOR VIOLA OPUS 53

Lise Berthaud, viola

QUARTET FOR CLARINET, VIOLIN, CELLO AND PIANO OP. 22

Stéphanie Carne, clarinet

Tchaika Trio: Elena Khabarova, viola / Sofiya Shapiro, cello

Alexandra Matvievskaya, piano

CELLO SUITE OP. 41

Ingrid Schoenlaub, cello

LIVE CONCERTS FESTIVAL "MUSICIENNES À OUESSANT 2016

SUITE FOR STRING ORCHESTRA OP. 42

The National Chamber Orchestra of Armenia, conducted by Vahan Mardirossian

Registered in Armenia

Total duration of the recording: 68'14

AR RE-SE 2017-1

Without the right expression, there is no poetry.

Théodore de Banville (1823-1891), Petit Traité de Poésie Française.

Approaching a composer's style is always a complex process. Very often, in the interests of classification, we assimilate what is a patient work of marquetry to the inventory of a few technical tools. But if these tools satisfy an immediate sense of understanding, they say everything but the essential, namely how the creative necessity disposes of them. More than the technical arguments themselves, it is the way in which the creator uses them that says a lot about the enigma that a style always remains.

In the case of Florentine Mulsant (born 1962), technique is present, of course, as a controlled necessity, but it remains strictly subordinate, as is the formal construction, to the expressive necessity or the poetic impulse. Neither the language nor any position regarding form, treatment of lines or timbre is an end in itself; they all intervene as the outcome of an emotional quest. It would be only a short step to imagine Florentine Mulsant's style as a smiling eclecticism, which would reveal a superficial listening on our part, to say the least. The composer's art cannot be reduced either to the anatomical description of her language foundations or to versatility in the choice of means. The firmness of the lines, the attachment to an interval and melodic perception, the cultivated sense of harmonic colour place Florentine Mulsant in the prolongation of the French School of the 20th century, from Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) to Henri Dutilleux (1916-2013). But one will look in vain for recourse to sonic or mathematical spells that would distract the listener from the fundamental expressive approach: if they are invoked, it is in total harmony with the poetics of the work. Another constant of this style is the modesty that constantly emerges in the pages of the present recital as in all those from the composer's pen. The intensity of a feeling is not measured by the extent of its sound staging, but rather by the perfect control of its exposition. Its depth will be all the more likely to touch the listener if a part is left to the art of the litote, to what is suggested rather than detailed. This in no way implies a music that is timid or wisely entrenched in half-tone; it reaches the heart, it touches, without ever forcing the line, the shores of the most extreme gentleness as well as those of the most direct vehemence, and nothing human remains alien to it. But she deliberately ignores the complacency or ease that make pathos a cover-up, however cleverly. Whether she uses post-serial elements, free atonalism, or more pronounced sonic polarities, Florentine Mulsant never loses sight of these necessities, which demonstrate both the constancy of a demand and the probity of an artistic commitment in which the heart commands the intellect without these two dimensions ever ignoring each other.

The Variations for flute and piano op. 11 from 1995 are a testimony to plasticity and formal demands. The work comes from a first version for clarinet and harp (1990), and exists in a version for clarinet and piano, as well as a final version for cello and harp (2006). The ductility of the melodic line links it, without any slavishness, to the lineage of the final sonatas (1915, 1916-1917) by Claude Debussy (1862-1918). The theme is both a supple cantilena and an intervallic reservoir (tone, minor third, semitone, tritone and right fourth) that the flute will present successively in several contexts, sometimes with an inversion of the direction of the intervals. The piano echoes, making the same material heard in harmonic aggregates, thus contracted. Variation I offers a pointillist breakdown of the theme, fragmented into intervalic incisions, with a close dialogue between the two instruments, intervening almost in relay of each other. Variation II, which is even more voluble, seems to be based on the sixteenth- and sixteenth-note strokes at the end of the theme, while continuing the play on the founding intervals of the theme. This element of coherence gives the work a quasi-modal euphonic colour: the opposition between dissonance and consonance, between tension and resolution, which is the basis of tonal language, gives way to an art of cameo, in which the sound aggregates appear as gradations of a dominant colour. The interplay of exchanges becomes denser until a slower breathing, preceding a final flight that seems to be suspended in its own resonance, like the crystal cage in which the fairy Vivian locks the enchanter Merlin in the air. Variation III is the heart of the work. Although the basic material (the true theme, as it were) remains eminently present, it is practically forgotten in favour of a dreamy intensity: a quasi-chorale in the piano supporting a flute line that moves from hesitation to deployment, leading to a more sustained, tenser discourse that, of itself, finally calms down without having broken the dreamy climate. After a virtuoso toccata in dialogue in Variation IV, full of mischief and capriciousness, Variation V gives the theme a reinforced primitive identity, solemnised by doublings (flute and left hand of the piano) and imitative effects. The original element seems to occupy all the space, in a subtle play of splits, reflections and shimmering that dissolves, like the shreds of a dream to which the awake sleeper preciously clings, into a final and mysterious resonance.

It was not until the twentieth century that the viola was finally given its first letters of nobility, through the concertante works of William Walton (1902-1981), Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) and Béla Bartók (1881-1945). Yet the instrument offers a very wide range of sound possibilities and expressive scope, even without the aid of an orchestra or a chamber partner. The Vocalise for Viola Op. 53 (2014), dedicated to its creator Lise Berthaud, is both a brilliant concert solo and a rigorously structured succession of three linked movements. The unity is based on melodic-rhythmic motifs that the composer mobilises with an apparent fantasia, underlined by the frequent alternation of tempi and an almost prescribed rubato. The viola is in turn low, light, poetic, tragic, malicious, but always a vehicle and dispenser of a lyricism characteristic of Florentine Mulsant's art: sober and intense, discreet as well as profound. The term "vocalise", if it clearly expresses the importance given here to the melodic phenomenon, should not be taken in its sense of exercise or complacent writing. Technical virtuosity (which the composer never renounces) never takes precedence over interiority, and it is indeed a lyrical poetry without words that we find ourselves faced with, summarising in its three sections the diversity of the human soul, from passion to contemplation.

The Quartet 'In Jubilo' op. 22 (1999, revised in 2002), dedicated to the clarinettist Stéphanie Carne, adopts a rare formation uniting clarinet in B flat, violin, cello and piano, which offers the composer a large number of original timbral combinations. Three movements follow one another, the first of which is in fact a series of linked variations, all based on the harmonic resonances of the piano (keys pressed, held, but not played, very present in the left hand). Here again, the notion of theme remains quite perceptible, but seen in the dual light of a melodic continuum and an interval series. The piano acts as a sonic envelopment of what the other instruments offer, nimbing them with a harmonic halo that takes nothing away from the precision of the discourse. The limpidity of the writing remains a primary necessity, which Florentine Mulsant never renounces. Seven variations follow one another, all marked by an almost lapidary conciseness and a progressive intensification of the dynamic palette, from the hieratic nature of the initial exposition to the most dizzying perpetual movement. The central movement turns to contrapuntal technique, with a series of imitative entries (cello, left hand of the piano, clarinet, violin in the opening section) based on a repetitive melodic-rhythmic motif. Once again, the melodic intervals used (a face-off between fourths and fifths, on the one hand, and altered fourths and fifths, on the other) take up the data inherent in the previous movement, with a concern for cohesion that is never at fault. The second part will see the reappearance of elements from the first movement (the tritone material in particular), while densifying the inter-instrumental exchange, which resembles a hiccup and presents a veritable mosaic of attack dynamics and playing modes. Counterpoint, at first presented - in its most classical sense - as a horizontal management of voices (hence the imitative technique), is gradually transposed to a timbral and quasi-playful conception, whose momentum cannot fail to draw the listener, even the most uninformed, into its wake. We are invited to a counterpoint of timbre, in which mastered technique remains at the service of a communicative expressiveness, art hiding art itself, according to the principle of Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764). The last movement closes the work on a more interior note. The piano is here the motor of a dialogue based on a descending scale, itself made up of an aggregate of minor thirds set into each other. The piano rests build the harmonic resonance of this mode, which seems to abolish dissonance to move in a secret and happy euphony. The other instruments gradually impose an ascending pattern on this motif, which becomes more widespread, while leaving the shadow of the beginning of the first movement hanging in the air. In a dreamy limpidity, the work closes almost like a cycle. If there is jubilation, as the title explicitly suggests, it is due both to the joy of creating, to an external manifestation, and to a more luminous and secret phenomenon, which is delivered with evidence and modesty in the last movement.

The 2012 Suite for Solo Cello Op. 41 is explicitly situated in a double descent, firstly that of the six suites by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) dedicated to the instrument, and secondly that of the three suites by Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) conceived for Mstislav Rostropovich (1927-2007) in 1964, 1967 and 1971, as a tribute to those of his illustrious predecessor. There is no question of pastiche or stylistic demarcation here, any more than with Britten. The very idea of a neo-baroque art form does not preoccupy Florentine Mulsant, at least not as a primary necessity. The suite draws its profound unity from an emotionally charged context, since the thematic material is based on the notes D - A - C - F corresponding to the letters of the composer's son PAUL, who died in 2011. The first movement revives the variation technique dear to the musician, since the initial statement of the theme (repeated, with modification of the last melodic interval) is followed by six linked variations that gradually unfold towards short rhythmic values. Far from being a lament, the movement unfolds in a luminous climate that is tempered, without ever veiling it, by a gravity that is all the more gripping for being underlying. The second movement is entirely realized in pizzicati and is marked by a playful joy. The material uses and transforms what was heard in the last bars of the previous movement, and the movement as a whole has an ABA' cut that makes it sound like a scherzo. The Fugue that follows has its subject based on the letters of the first name PAUL, each marked by a long value at the beginning of the bar, with a melodic commentary between the values. Despite the technical difficulty inherent in the monodic character of the instrument, which must be applied here to polyphonic writing, it is limpidity that remains the cardinal virtue here, serving the expressive progression up to the stretto that occupies the last third of the movement, before the calm exposition of the transposed subject in the last bar. The fourth movement, the true beating heart of the Suite, adopts a more melodic character, and is based on the presentation of the last bar of the Fugue, which becomes a modest but vibrant ascending call, followed by a disinence that is both noble (in its dotted rhythms) and overwhelmed. After a central section based on this inflection, supplemented by harmonic or melodic fifths in the low register, the initial figure reappears, gradually reduced to its essence as a fifth, strikingly present even in its effacement. It is not on a funereal note that the work closes, so much so that the presence of departed loved ones is a luminous companionship. Joy dominates here, in a spirit akin to a jig, with the theme-first name still omnipresent in a new presentation. The last five bars close the work with a reminder of the first movement, witnessing a gentle presence that transcends emotional or affective states, and which makes this Suite a vibrant opus of intensity and restraint.

The Suite for string orchestra op. 42 (2012) is not a descendant of the neo-Baroque suite, nor is it a pastiche. The contrast between the tempi of the five movements and their secret kinship bring it closer to a symphony, but it retains the idea of contrast, of changing moods that do not imply a disjointed structure or thematic mesh. The first movement (quarter note = 56) contrasts two founding ideas:

- the first consists of a progressively enlarged interval series, gradually expanding towards the treble, before a more rapid decay. As is often the case, Florentine Mulsant retains the clear perception of a melodic line, but this is based on interval work that lends itself to transposition.

- the second, less voluble (bars 15-24 for the first presentation), has a more static aspect. The technique of enlarging the intervals, the choice of intervals and the varied repetition of the idea nevertheless link it to the first idea, to the extent that the two constitute two faces of the same entity.

Preferring here the close alternation of the two thematic supports to the option of a scholastic development, Florentine Mulsant makes this face-to-face encounter the formal motor of the movement, before the sudden return to silence.

The next movement, which is noticeably slower, is based on airy oscillations in the upper registers, which support a theme initially entrusted to the cellos and double basses, directly derived from the first idea of the preceding movement, and endowed with a long disinence. A transitional figure will link the transposed appearances of this theme, which uses, among other things, the sequences of fourths at semitone intervals dear to the composer. Initially proposed in a homorhythmic and harmonic configuration, the theme is gradually expanded to include non-regular imitations and interval variations that lead first to an emotional climax and then to a discreet quivering of the violins I that closes this intense and mysterious page. The very lively third movement evokes a Mendelssohnian scherzo in its lightness. We find the transitional motif of the second movement, the semitone oscillations that marked the first idea of the first movement, the founding intervals of the main themes already heard. The term "Suite" in no way denies this cohesion of material within the work, which is a constant in Florentine Mulsant's creative process. Precise Very expressive, the fourth movement unfolds a broad theme with an obsessive rhythm, progressing in stages, always working on the same intervals. The piece is presented as a succession of arches, each time seeing the theme start from the low stratum to reach the high or the mid-range. The choice of an obstinate rhythm gives the movement a haunting, almost litanic character. The last movement recapitulates the material of the work in a lively dialogue. The limpidity of the discourse and the clarity of the formal design allow the Suite to end in a burst of light.

Subtlety and discretion, frankness and modesty, clarity and in-depth elaboration of structure, the coexistence of a melodic preoccupation and interval coherence, Florentine Mulsant's style combines, conjugates in the most intimate way and renders complementary apparently antithetical phenomena. It is indeed an alliance and not a marriage of reason, which takes place with a naturalness that it would be futile to try to reduce to this or that phenomenon of technique, influences or school: it is precisely in this consubstantiality that lies, palpitating and secret, the soul of the style of one of the most endearing figures of French music of our time, of which the present recital offers a panorama, if not complete, then at least representative, for our greatest pleasure.

Lionel Pons

The press speaks about it

The artist's note!

"Subtlety and discretion, frankness and modesty, clarity and in-depth elaboration of structure, the coexistence of a melodic preoccupation and interval coherence, Florentine Mulsant's style combines, conjugates in the most intimate way and renders complementary apparently antithetical phenomena. It is indeed an alliance and not a marriage of reason, which takes place with a naturalness that it would be futile to try to reduce to this or that phenomenon of technique, influences or school: it is precisely in this consubstantiality that lies, palpitating and secret, the soul of the style of one of the most endearing figures of French music of our time, of which the present recital offers a panorama, if not complete, then at least representative, for our greatest happiness.

Lionel Pons