Product details

String Quartet No. 14, Op. 105, B. 193

Piano Quintet No. 2, Op. 81, B. 155

Total duration: 74'45

Sound engineer: Jean-Marc Laisné.

Recorded at the ADAC Auditorium,

place Nationale, 75013 Paris,

on 5, 6, 7 and 8 June 2006.

Booklet: Nicolas Southon.

AR RE-SE 2006-2

Summary

Antonín Dvorák: Treasures of a Bohemian Life

April 1895. After two and a half years in the United States, Antonín Dvorák (1841-1905) returned to Bohemia. The Czech composer's American sojourn is one of the most famous episodes in his biography. It was in his New York home, where he lived with his wife Anna and two of their children, that he composed his best-known works: the so-called "New World" Symphony No. 9 (Op. 95, B. 178, 1893), and the "American" Quartet No. 12 (Op. 93, B. 179, 1893). To these should be added The American Flag (Op. 102, B. 177, 1894), the so-called "American" Suite for piano (Op. 98, B. 184, 1894) and the 3rd String Quintet, known as the "Indian" (Op. 97, B. 180, 1893), to complete the list of works inspired to Dvorák by Afro-American or Indian musical traditions and mythologies. The use of pentatonic melodies, themes similar to negro spirituals, syncopated rhythms or those reminiscent of Indian traditions, and natural minor harmonies are the elements of local colour that mark these pieces. With American or Indian folklore - as with Bohemian folklore - Dvorák was careful to reinvent rather than borrow: "I simply wrote personal themes, giving them the particularities of Black and Redskin music," he explained.

Dvorák had been called to the New World by Jeannette Thurber, a wealthy music lover who wanted to create a conservatory in New York worthy of the one in Paris, where she had once studied. A few years after the opening of her establishment, the patron wanted to place a charismatic and renowned personality at its head, secretly wishing to encourage the emergence of a national school of composition. In 1891, she had the idea of contacting Dvorák, the Czech composer whose prestige had been growing since his Slavonic Dances (Op. 46, B. 78, 1878) and his Stabat Mater (Op. 58, B. 71, 1877) had been celebrated throughout Europe at the end of the 1870s. Not without hesitation, the composer responded favourably to the contract offered to him. In doing so, he took up the challenge of a new life, rather than enjoying the comfort and European successes that were already guaranteed. In the years that followed, Dvorák ran the American School of Opera in New York, taught composition, conducted concerts, composed new works, and discovered a musical tradition that was unknown to him. He surrounded himself with talented students and succeeded in winning over the Americans with his dynamism and talent. The exile was soon crowned with success. So much so that after having honoured his first contract, the composer signed a second one in April 1894, which provided for the renewal of his engagement until the spring of 1896. Between May and October 1894, Dvorák took a break in his native Bohemia, before leaving for his new American season. But from then on the auspices seemed less favourable to his serenity.

Indeed, there was a steady stream of setbacks that affected the musician's morale and creativity. After receiving bad news from his father, who was ill and isolated in Velvary, Dvorák learned at the end of the year of the death of his close friend Marie Cervinková-Riegrová, author of the librettos for his operas Dimitri (B. 127, 1882) and Jakobín (The Jacobin, op. 84, B. 159, 1888). A few months later, he received alarming news from his beloved sister-in-law Josefina. Added to this were the worries caused by his 2nd Cello Concerto (Op. 104, B. 191), which was still in the making and whose soloist demanded that certain passages be modified. Finally, it becomes clear that his mother-in-law is now too old to take care of her four grandchildren back home. The Dvoráks returned to Prague in April 1895 to support Josefina. Dvorák's sister-in-law, with whom he had been in love before marrying Anna, died in May. All these events shook the musician: American fame was of little consequence compared to his loved ones and the importance of his roots. He breaks the contract with Jeannette Thurber; he and his family do not return to the United States. Back in Vysoká, he returned to a quieter way of life, between a chosen social life and solitary walks along his favourite paths.

From the New World to Bohemia, or the return to the self

Dvorák has not composed anything since his Cello Concerto. There is, however, the beginning of a string quartet, sketched out on 25 March in New York, shortly before his departure. The musician did not work on it for the moment, because he was busy with a brand new work, also a quartet, from 11 November to 9 December: it would be the 13th (opus 106, B. 192). In the meantime, Dvorák finally took up the New York sketches. On December 30, they became the 14th String Quartet (opus 105, B. 193). Completed after the 13th Quartet, the 14th was thus projected before it - which explains the reversed opus numbers. These twin works, both of true conceptual grandeur, testify to a new-found serenity and inspiration: 'After three years we are happy to be able to spend the merry Christmas holidays in Bohemia, whereas last year in America it was different, where we were so far away, separated from our children and our friends. But God gave us this moment and that is why we are all so happy. I am now hard at work. I am working with such ease that I could not have wished for more," Dvorák wrote to a friend on 23 December. And it is probably no coincidence that his return to composition after his return to his homeland was through the purifying genre of the string quartet. After many torments, and while he had not taken up a pen for several months, Dvorák renewed his creativity through what is the essence of musical writing. Indeed, one cannot insist on the virtues generally recognised in the quartet, the most demanding and serious of the genres of Western art music, especially since Beethoven devoted his most visionary inspirations to it. The string quartet is a privileged place for experimentation, but it can also be the crucible of a stylistic perfection that seeks synthesis rather than novelty; this is the perspective of Dvorák's 13th and 14th Quartets. After the trip to the United States, it is also a question of warding off the American colouring that was clearly evident in the 12th Quartet. In Op. 105, nothing stands in the way of musical thought, the writing is pure lyrical movement, stripped, or almost so, of all anecdote, free of any concern other than that of harmoniously combining four melodic lines. The 14th Quartet appears to be a farewell to America: its foundations were laid there, but its musical substance never refers to it. Through the transition it makes between the New World and Bohemia, it is, as has been said, a work of return to the country, but also a work of return to oneself. The quartet was premiered on 16 April 1896, the anniversary of Dvorák's return to Bohemia, at a concert for students of the Prague Conservatory at the Platyz Hotel. The 'official' premiere, by the famous Rosé Quartet, took place in Vienna on 10 November 1896. On December 20, the work was revived by the Dannreuthe Quartet in New York, and on January 21, 1897 by the highly regarded Bohemian Quartet in Prague (on second violin was the composer Josef Suk, Dvorák's future son-in-law, while on cello was Hanus Wihan, the Concerto's capricious creator). Barely three months later, his protector and dear friend Johannes Brahms died. His death marked the end of an era, one that had seen Dvorák's first steps and rise to great success. In the seven years remaining to him, the Czech would return to the genres he had cultivated in his youth, mainly opera and the symphonic poem.

Quartet No. 14 (Op. 105, B. 193)

I. ADAGIO MA NON TROPPO - ALLEGRO APPASSIONATO. On a dark and sinuous motif, the instruments appear one by one, from the lowest to the highest. The imitative process signals the creation of a world in miniature (until 00'23), in the shadowy key of A b minor: nothing less than a slow introduction, an introductory section once characteristic of classical structures, and even of the symphonies of Schubert or Berlioz. Unstable and groping, this Adagio ma non troppo leads to the affirmation of the first theme (1'13), Allegro appassionato. It is nothing other than the mutation of the initial sinuous motif: indecision has become determination, shadow has become clarity. The heaviness of the introduction is met by a melody that soars in the official key of the work, Ab major. As a complement, a second melodic incision, even more lilting, soon appears (1'31); we will find it again. What we have heard since the end of the introduction constitutes the exploration of the first tonal zone. This is now the transitional episode to the second: a more offensive dialogue is established between the cello and the two violins (1'47), who reconcile on the first theme (1'59), then resume a calmer dialogue (2'15). The second tonal zone then opens, in the key of Eb major (dominant of the main tone, as it should be): a cavalcade begins (2'29), supported by the cello which hums in the low register. The mechanics are perfect, one imagines a warrior in combat, striking his blows, withdrawing, returning, then triumphing (2'55). After the whole of this exposition, a Poco sostenuto e tranquillo (3'11) opens the development. This essentially exploits the sinuosity of the first theme, which serves as both main line and accompaniment, in an impassioned discourse, carried away by its perpetual sixteenth notes. The complementary melody of the first theme resurfaces and calms the game (4'49). Its premature return signals the imminence of the recapitulation: the first theme, almost imperceptible, fades out (5'22). As in the exposition, the dialogue between the cello and the two violins (5'47) announces the second section, no longer presented in E flat, but in the main key of A flat (this is the rule of the recapitulation). The cavalcade (5'58) is just as admirably graded as the first. There remains the Meno mosso of a 'Coda' (6'37) to combine the first theme with the melody that supported it, before closing the first movement with panache.

II. MOLTO VIVACE. This is the fast movement of the quartet, in traditional form: Scherzo/Trio/Scherzo. The Scherzo is similar to a furiant, the Czech folk dance, made picturesque by its shifting rhythmic accents. In F minor, a mischievous rhythmic motif is imposed from the outset - its abrupt ending (0'06, 0'15) becomes a theme in itself (0'18, 0'31). In a writing that abounds and rustles with a thousand extraordinarily arranged details, it is a popular spirit that dominates, transcended however by a dazzling technical mastery - rhythmic in particular. The last section of the Scherzo takes up its main motif (1'17). In the Trio, quieter by nature, and set in the neighbouring key of Db major, Dvorák borrows the lullaby 'That sweet child's smile' from his opera Jakobín. The warm melody, supported throughout the section by quivering chords, gives no hint of its dramatic origin. It begins with a dialogue with the cello (1'43), modulates (2'49), and is even treated as a canon (3'31). After a quasi-love duet between the two violins (3'45), a calmer section (4'27) brings the Trio to an end, which signals the return of the Scherzo with the recall of its main motif (4'45). The second statement of the Scherzo will be identical to the first, simply with the addition of its repeat bars.

III. LENTO E MOLTO CANTABILE. In truth, this movement in "Lied" (ABA) form is more fervent and lyrical than truly quiet. Very classical in the arrangement of its phrases, it is nonetheless conducted in a very romantic manner by the effective gradation of its outpourings. A first theme is given, tender and ample, already enriched by an additional line when it is repeated (0'43). Even more tender, a second theme suffers the same fate, first given distinctly to the first violin (1'26), then magnified by the addition of a new voice and various ornaments during its second exposition (2'28). As can be seen, the process consists of exacerbating the expressiveness by means of repetitions and variations. In the central, more sombre part, an ostinato in the cello (3'49) supports an anguished inflection in the violins and viola; the writing is reversed, the ostinato moving to the high register (4'29). Carried away by the chromaticism, the discourse becomes more ardent (4'55), then quickly calms down. The return of the first section is initially marked by the presence of pizzicati (5'28), but especially by the rustling of the second violin. The course is markedly different from the first presentation: one passage is absent, but above all, the richness of the ornamentation brings the discourse to heights of effusion. A coda (7'38) brings back the anguished motif of the central section, like a bad memory that is finally erased by the serene progression in the high register of the first violin.

IV. ALLEGRO MA NON TANTO. The last movement of the quartet is by far the largest. Its formal complexity would make a linear description laborious, but some of its particularities must be emphasized. First, its thematic economy. This vigorous and incredibly inventive page is based on a single motif - or almost a single motif, laid bare in the cello at the opening. In the midst of its many developments, it will return to the violin (4'06) or cello (4'47) and stretch the discourse. Let us also note the presence of a quiet song (1'53) which will make its return transposed towards the end of the movement (6'20). A sign that the rhetoric of sonata form is not absent from this movement, even if the lively and playful trappings of a rondo define it above all: contrasts, relaunches, crossfades of sections, swirls of sixteenth notes. It is under the sign of this luminous gaiety that Dvorák bids farewell to the quartet and to chamber music.

Redeeming a "youthful sin".

Back to the past. As has been said, the 1880s were the years of Dvorák's first great successes. England gave him a particularly enthusiastic welcome. The musician went there several times between 1884 and 1886, for example to conduct his Stabat Mater (at the Royal Albert Hall, in front of 12,000 people), his 6th Symphony (Op. 60, B. 112, 1880), his Nocturne for string orchestra (B. 47, 1882). It was also here that he premiered his 7th Symphony (op. 170, B. 141, 1885), his oratorio Saint Ludmila (op. 71, B. 144, 1886), and his cantata Svatebni kosile (The Wedding Shirts, op. 69, B. 135, 1884). These tours were profitable, while Austria and Germany took a dim view of Dvorák's musical nationalism. Indeed, the composer described himself as "a simple Czech musician, who hears music everywhere around him: in the forests, in the wheat fields, in the water of the streams, in folk songs... Nature, stories, are the source of my inspiration. Praise my music, but the most important thing for me will be what people think of it here in Bohemia; I will be touched and happy if it is received with love.

In 1884, the composer acquired a property in Vysoká, south of Prague. From then on, he spent part of the year there, from spring to autumn, alternating between composing and walking in the forest, talking with the local peasants or welcoming his musician friends. The serene, family atmosphere of these stays in South Bohemia was indeed conducive to the development of a rich and varied chamber repertoire. In this production, Dvorák reveals a face that is still relatively unknown to us. His Bohemian romanticism, hitherto divided between Brahms and the more modern school of Liszt and Wagner, is illuminated by a classical purity and serenity that will become one of his trademarks. Alongside new projects (notably the Mass in D, Op. 86, B. 153), the composer immersed himself in his first scores in 1887. He thus revised his 1st String Quartet of 1862, still unknown to the public, and transcribed for string quartet twelve melodies from the cycle The Cypresses (B. 11), which arose in 1865 from his passion for Josefina Cermáková - older sister of his future wife Anna. Dvorák also sought to find the manuscript of his Piano Quintet of 1872 (Op. 5, B. 28), one of his most successful early compositions. To the friend who had inspired its creation, he asked for a copy of the manuscript, explaining: "At the moment I like to take a look at my youthful sins. Dvorák himself was surprised at the invention of the work, although he found certain faults in it: it was too talkative, imperfectly structured, and sometimes overly loud. And the revision he made of it did not entirely satisfy him. His dissatisfaction led him to start work on a work with an identical formation and tone. Between 18 August and 3 October, his 2nd Piano Quintet (Op. 81, B. 155) was born - or how the atonement for a "youthful sin" gives rise to one of the masterpieces of chamber music! It was premiered on 6 January 1888 by Karel Kovarovic on piano, Karel Ondrícek and Jan Pelikán on violins, Petr Mares on viola, and Alois Neruda on cello, at the Umelecká beseda (Artists' Union) - a society in which Dvorák had been a member since its founding in 1863. At the same concert, the string quartet version of the Cypresses (B. 152) and the 1st String Quartet (Op. 2, B. 8) were also given their first performance.

Piano Quintet No. 2 (Op. 81, B. 155)

I. ALLEGRO MA NON TANTO. This movement, whose strength and perfection have often been compared to Schubert's Trout Quintets and Schumann's Op. 44, is in sonata form.

The first theme, sung by a lyrical cello and supported by the silky undulations of the piano, immediately grabs the listener (the writing is reminiscent of the opening bars of the Quintet Op. 5). Its curve is generous, noble, leading from the main tone A major to its namesake A minor. In response, the quintet bursts into flames (0'32) and takes the listener to more distant tonal regions. It seems that this is to bring back the initial theme, in the piano (1'23), warmly supported by the strings. False alarm: it is the violin, in the high register, that takes charge (1'37). As before, the quintet responds with a more agitated episode (2'04), which takes on the appearance of a tarantella with its triplets. This transition allows the second theme of the movement to reveal itself, more pathetic than the first, in C# minor: first in the solo viola (2'32), supported by the anguished beats of the piano, then in the violin, accompanied by all the other instruments. A variation follows (3'03), swelling with lyricism; a moving but short-lived passage, contradicted by more tormented motifs (3'15). In all the strings (3'55), this second theme finally reappears vigorously, in peroration of this exposition - entirely repeated, in accordance with the repeat bar indicated by Dvorák. Opening with ghostly piano arpeggios that Brahms would not have disowned (8'14), the development builds on the first theme (8'30) to colour the harmonies with expressive modulations, and then on the most agitated version of the second theme (9'11). The transitional sections of the exposition are not to be outdone, and also provide material for variation (9'42). The discourse calms down (10'39) and the first theme reappears (11'04) through an exchange between piano and viola that increases in intensity, bringing the theme to incandescence (11'25). A way of calling the recapitulation (11'41), deprived of the initial statement of the first theme in the cello. Is it a coincidence, then, that the cello (and no longer the viola) is given the task of intoning the second theme (12'35) - now in the key of F# minor? Except for these details, the course of the recapitulation is comparable to that of the exposition. Ghostly arpeggios introduce a final development (14'11), which completes the exploitation of the potentialities of the second theme, now proclaimed in a heroic tutti (14'26), before a jubilant and almost popular coda (14'43) closes this page of quasi-symphonic power.

II. DUMKA. ANDANTE CON MOTO. The slow movement of the Quintet is in Rondo form: ABACABA (the A section thus taking the place of the refrain). The title defines this page as a Dumka: only the refrain can actually claim to be inspired by this Ukrainian ballad, nostalgic and recitative-like (Dvorák is also known to have used it in his famous fourth Piano Trio, 'Dumki', B. 166, Op. 90, in 1891).

Opening this movement with its poetic force and admirable expressive contrasts, the 'A' section unfolds a poignant theme in F# minor. Its eloquence, as well as the sobriety of its accompaniments, suggest a stylized recitative. The keyboard, viola and violin exchange their respective phrases, set in textures of extreme delicacy. The atmosphere is elegiac, but also a certain gravity - one thinks of Schumann's In modo d'una marcia from Op. 44. Rarely has the piano been so sparing with its resources; the octaves it plays in counterpoint to the quartet are simple but beautiful. A transition (2'20) leads to the D major of the 'B' section, Un pochettino più mosso: the two violins launch into a radiant duet (2'38), wrapped in a texture that is enlivened by the pizzicati of the cello and viola, as well as the low chords and arpeggios of the piano. A second episode follows (3'22), with fairly similar textures, although the piano melody dominates. Without transition, the refrain "A" returns (4'31). Its flow is almost identical to its first statement, but the instrumental roles have been switched: in short, the quartet sings and the piano punctuates. Although short in duration, the central 'C' section provides a salutary contrast in this long movement. Supported by the almost 'heartbeat' of the piano (6'57), the strings launch themselves one by one into a vigorous, dancing Vivace in F# major; note that its theme is a spectacular metamorphosis of the initial motif of the refrain. At a sudden break (7'38), a more identifiable version of this motif calms the game and reintroduces the "A" section (7'51). The writing is different again: the violin and viola duet is accompanied by descending arpeggios from the piano and punctuations from the second violin. In the continuity, the "B" section reappears (9'14), this time in F# major. Finally, the chorus returns (11'06). More tender than ever, it presents yet another different instrumental distribution, then sinks into the low register to close this movement.

III. SCHERZO. (FURIANT) MOLTO VIVACE. The Furiant announced by Dvorák (a lively Czech folk dance) should be thought of as a fast waltz, in the tradition of those written by Schubert (one could also evoke the Scherzando of Op. 100, though not as fast). The frenzied writing of the tripartite movement (ABA) contrasts perfectly with the emotion of the preceding Andante.

Three melodic elements animate its first 'A' section. The main one is stated at the outset, in the quartet alone, and then instantly taken up by the piano: alert and joyful melodic volutes soar into the high register with insouciance. The second element is a popular-looking song taken by the cello (0'12). It is completed by a variation of the scrolls (0'21), which take on their full rights (0'29). Then comes the third, calmer element, in the viola (0'42), the second violin (0'56), then the piano (1'11); the volutes do not hesitate to punctuate it (0'52, 1'07), giving unity to this thematic mosaic. They conclude the first section of the movement with panache (1'21). The chords of a lulling chorale set the soothing climate of the central section "B" (1'43). The languid volutes are taken up again by the viola (1'52), the violin (2'08), and then the piano (2'12). On the harmonies of the "chorale", a new tune appears, first in the viola (2'32), then in octave in the violins (2'49). The volutes reappear and dialogue with the chorale (3'04). An acceleration brings back the first "A" section, now deprived of its third melodic element.

IV. FINAL. ALLEGRO. The exuberant last movement of Dvorák's Quintet is structured as a rondo sonata. In other words, and in an attempt to keep it simple, the two themes of a usual 'sonata form' are arranged to give the impression of alternating characterised episodes and a refrain. The whole thing follows the well-known rhetoric of giving the second theme in the main key in the recapitulation, whereas the exposition had stated it in the dominant. So much for the theory. The practice is both more pleasing and even more complex. How can one describe the incredible invention that Dvorák displays throughout this Finale? Let us mark out the main elements of the discourse.

After an introduction, the first theme is intoned by the first violin (0'11), in A major; it is virtuosic and dancing (some commentators compare it to a polka), already developed, repeated several times, and mixed with the motif of the introduction. After a transition that gives pride of place to the pianistic features (0'43), it is again the first violin that takes charge of the second theme, given in E major. It is made up of several episodes: a piquant and accented phrase (1'18), another magnificently lyrical phrase (1'31), a strange and sweet punctuation element (1'40), a passage bathed in syncopations (1'56), the punctuation element again (2'08). The introduction returns (2'28), and summons the first theme to follow (2'39) - the beginning of the development in 'sonata form', the return of the refrain in 'rondo'. Mixed with the motif of the introduction (2'48), it gives rise to multiple developments, where virtuosity vies with the variety of moods. The mechanics slow down (3'35), a curtain of mystery appears (3'35), which rises on a formidable fugato (3'39): the instruments in turn sing the first theme. The tension is at its height (4'16), and it is now a question of bringing it down without losing intensity. The first theme returns on a pedal note in the cello (4'20), then a chorale is heard (4'37), a curious moment of recollection, a spectral and superb invention in the middle of this apotheosis of the dance. A few more snatches of the first theme (4'42), a murmur of trills, and the second theme returns (4'59), made up of its various episodes, now stated in the key of A major. The mysterious chorale reappears, predicting the end of the movement. Solemn and peaceful? This would have been without counting on the turbulent first theme, which at first calms down in the vicinity of the chorale, but eventually regains its pride.

Nicolas Southon

The press speaks about it

![]()

Le Monde de la Musique, December 2006, Patrick Szersnovicz

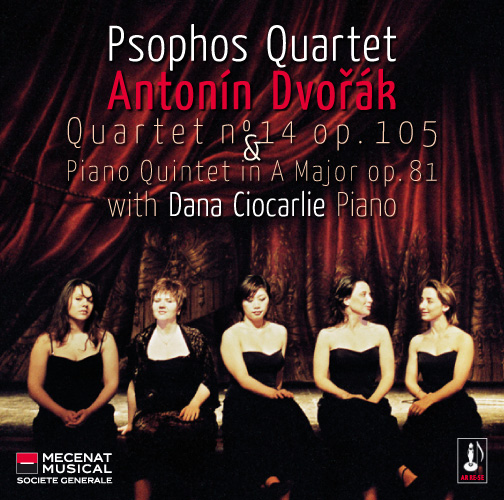

"After writing a First Quintet for piano and strings in A major in 1872, which he himself was disappointed with, Dvorák composed his Quintet in A, Op. 81, in 1887. This score, one of his best, reflects a unique optimism in this repertoire. Beautiful as it is fragile, the work cannot quite be compared with the greatest quintets for piano and strings (Schumann, Brahms, Franck, Fauré, Schmitt, Shostakovich), but it has achieved the same degree of fame; it owes something to Schubert and Schumann and much to Brahms, though its Slavic inflections are its own. Planned before the 13th Quartet but completed after it, the 14th Quartet (1895) is Dvorák's final chamber score. Although constructed in four movements, the work returns to the pre-classical order, with the scherzo in second place. The final rondo-sonata is particularly well developed, beginning in the cello's lowest register and ending with an overflow of joy. Winners of the First Grand Prize of the Bordeaux International Competition in 2001, the young musicians of the Psophos Quartet lead the 14th Quartet with a broad gesture, imposing a free and precise discourse, made of melancholic inflections and sudden outbursts. The cohesion of the ensemble is exemplary, rather distant from the Czech accents, but keeping lightness and transparency. The collaboration with the young Romanian-born pianist Dana Ciocarlie produces an interpretation of the Quintet op.81 remarkable for its nostalgia and balance.

CD produced with the support of Mécenat Musical Société Générale