Details

Sonata No. 1 Op. 28 in D minor

1.Allegro moderato

2.Lento

3.Allegro molto

Sonata No. 2 Op. 36 in B flat minor

4.Allegro agitato

5.Non allegro - Lento

6.L'istesso tempo - Allegro molto

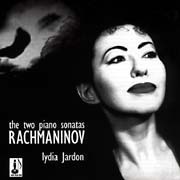

Recorded at the Théâtre de Poissy, 15, 16 September and 2 November 1999

AR RE-SE 2002-4

Fin de siècle: A total opera

The 19th century ended with a fertile anxiety and in all domains, the era was looking for a style and a face. Debussy celebrated the 1900s with Pelléas et Mélisande. Art Nouveau in France and the "Jugendstil" in Germany gave birth to a world of objects and motifs without relief, from which the figures of the animal and vegetable world sprang up. In painting, Fauvism, Cubism and Futurism exalted a colourful struggle between colours, graphics and the tumult of bodies caught up in expression. In architecture, the construction of the Sagrada Familia, Antonio Gaudi's Barcelona cathedral, reveals a religious building with volcanic forms set with mineral colours, with iron ramps that are twisted by the multiple convulsions of the material.

From 1900 to 1913, rhythm was universal and the plastic arts went hand in hand with music. As the first Russian ballets and their shimmering harmonies swept through Paris, industry and machinery captivated architects and decorators, who immediately developed a romantic passion for them. In 1912, Schönberg's Pierrot Lunaire and the sonic mysteries of atonality resonated in Vienna. Finally, Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, the forerunner of jazz, regenerated the era after the Great War and turned percussion into a rhythmic act. The 20th Century is thus revealed as a score in which each voice embodies a singular art taking its place in the universal polyphony. This explains the "musicalist" attempt of Kandinsky and Kupka: to create a total opera by putting music in painting, where the decor enters into the balance of the score, to create a visible link between the body of the painter on the lookout for colours and that of the performer perceived as a resonance chamber where rhythms and melodies resound.

At a time when this era was asserting itself and shining, Rachmaninov was considered a musician of the past, a folklorist of the Russian soul in the tradition of Anton Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky. His determination to defend a romanticism submerged by the rising atonality seems like a rearguard action. Does he not denounce Debussy and Prokofiev for "their absence of melody"? He proclaimed that "the heart is becoming an atrophied organ, that it is no longer used, that it will soon be a mere curiosity". Yet Rachmaninov loved jazz. In 1924, he was fascinated by Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue and gave it a standing ovation in New York with Stravinsky, Heifetz and Kreisler. In 1915, during a series of concerts devoted to Scriabin, Rachmaninov returned to the other side of his genius: the art of the piano. Until the age of 70, he would occupy the front of the stage. He is a force of nature whose fingering is a lesson in interpretation, the surest way to explore his instrumental vision. His hand can cover twelfth intervals without any note suffering. The character of each finger always comes through clearly, and each gesture is embodied in perfect harmony with the musical meaning. For Rachmaninoff, a successful performance must lead inexorably to the point of balance of the work built around a central axis where the architecture and vigour of the score are concentrated. The pianist's role is to build his performance in order to reveal this point with the greatest naturalness by arousing this "germination of the fingers" fertilising the keyboard and whose impetus, in Rachmaninov's own words, "has the effect of a ribbon that tears at the end of a race.

The music of an "emotional athlete

The two sonatas written between 1900 and 1913 are an extravagant example of his pianism and his sound universe. They illustrate the struggle of a composer who is rediscovering his instrument by bringing the art of the piano into the mainstream of the century. Rachmaninov pushed the instrument to the limits of its possibilities. It is the creation of an "affective athlete" in the sense of Antonin Artaud: a pianist who, through composition and interpretation, "uses his affectivity as a wrestler uses his musculature".

In these two sonatas, Rachmaninov has been accused of eschewing simplicity in favour of a profusion of effects and ornamental profusion, but let's give the floor to Lydia Jardon: "In these two works, the performer is confronted with monumental phrases, and despite the enormous overloaded left hands, he must bring them to life without drowning in the decomposition of themes. One cannot bring everything to life without sacrificing the preponderance of the right hand's singing, which is haunted by a kind of cerebral orientalism. At the beginning of my work, these repetitive phrasings and harmonic obsessions left me perplexed. I wondered how I could inhabit this exceptional density of the score without creating boredom when the same themes in different keys recur unceasingly in the second, and even more so in the first. There are basses in these two sonatas that are found even in the last notes of the piano. It seems to me that the danger would be to give them an importance that would harm the cohesion and balance of the sound and would make the building more noisy than expressive. To avoid this, I was determined to construct the whole performance as a true study of sounds."

Sonata No. 1

Rachmaninov himself found it interminable. The work is a synthesis between the romantic sonata shaped by Schumann and Chopin and the programme symphony modelled on Liszt's Faust Symphony. In Dresden, he wrote to his friend Morozov that its dimensions were linked to the main idea: "Through each movement, three contrasting human types emerge in turn: Faust, Margarita, Mephisto. He even considered adapting it into a symphony, but the purely pianistic style of the work resisted orchestration. Jacques Emmanuel Fousnaquer wrote that "this sonata is a body of sound in perpetual ebullition, an absurd and sulphurous poem" in the middle of which the familiar theme of the Dies Irae emerges. Rachmaninoff would use it often during this period in Dresden, where he composed the Second Symphony and the Isle of the Dead, inspired by Arnold Böcklin's painting. The first movement invades the ear like an improvised fantasy on fifths and seconds. The second movement closes in on itself as if Rachmaninov had deliberately wished to erase all thematic contrasts in order to enter into himself through a closed sound world. The melody of the theme is based on the play of seconds around a repetitive key in the manner of ancient Russian church music. The virtuosity of the third movement overwhelms the listener and destroys any form of relief. It emphasises a length that is woven together by an inexorable pulse based on the total mastery of polyphony.

Sonata No. 2

Composed in Rome when he had postponed the orchestration of Les Cloches until the following summer, Rachmaninov compared this sonata to Chopin's Second Sonata, "which lasts nineteen minutes and says it all...". It is in the same vein as the first sonata: the same three-part structure, the same counterpoint, the same profusion of ornamentation in the service of rhythm. Jacques Emmanuel Fousnaquer writes: "A strange telluric vigour emanates from the first and third movements, from which the Prokofiev of the 'war sonatas' could well emerge. In 1931 Rachmaninov tried to give it a more ethereal version. Horowitz produced a third version in 1942, which was a synthesis of the first two. It is the 1931 version that Lydia Jardon has restored to us.

Richard Prieur

The press is talking about it!

"The versions of the two sonatas by Weissenberg and Paik are no longer available, so the great references for these two opuses in a single CD are the work of two female interpreters. Idil Biret has indeed signed a beautiful version of these works, alas! hampered by a rather harsh sound recording. Lydia Jardon's recording cannot be faulted on this point: anyone who has savoured her full, timbred sound in concert knows how faithful the microphone is here. Some people talk about fingers and effects in Rachmaninov; Lydia Jardon responds with song, poetry and attention to timbre. From Sonata No. 1 - which is not without its weaknesses, Rachmaninov was the first to admit it - the artist does not demand more than this opus can offer and that is why she is so captivating. There is nothing forced or unnecessarily spectacular in her conception, but a simplicity that releases the Faustian essence of the text and plunges us into a wonderful poetic journey - where the feeling of freedom is never the result of easy abandon. Lydia Jardon's polyphonic sense (what a technique it takes to achieve such clarity!) imbues the discourse with relief, an incessant vibration... and gives us hope for a fabulous Sonata No. 2... It has been said: gratuitous pyrotechnic demonstration is not the subject here. The authority with which Lydia Jardon attacks the Allegro agitato is that of a performer who has decided to charm - in the magical sense of the word - the work rather than to set it on fire. The sheer nobility of this approach will delight lovers of this repertoire, as much as it will lead its detractors to revise a number of prejudices. The nobility of the middle movement (so many ivory grinders offer here a moonlight chromo at the edge of the Nile), speaks volumes about an interpretation that renews our perception of the work. As much as the late Sergio Florentino (APR, Diapason d'or) was able to do, that is to say... ".

March 2003, Alain Cochard

![]()

"Six years (1907-1913) separate Rachmaninoff's two Piano Sonatas (the Russian composer's only contributions to the genre), and in a few years he will have achieved a mastery of form and ideas. If the composer found the First Sonata 'interminable', he compared the next one to Chopin's Second Sonata 'which lasts nineteen minutes and says it all'. Breaking the unity of the whole, illuminating the peripheral motifs in an overly fragmentary way leads to the disintegration of the score. Blurring the intertwining of motifs, the specific build of each rhythm, leads to the opposite result, which is no less damaging. Two pitfalls avoided by Lydia Jardon who imposes herself by an extraordinary digital mastery, by a precise and supple playing power, and by a musical line management integrating the density of the thought with for corollary the extent of the dynamics and the need to preserve the coherence, the sound balance for the benefit of the right expression without affeteria in the slow movements for example. With such eruptive music, "in perpetual ebullition", Lydia Jardon joins her illustrious colleagues Weissenberg (Deutsche Grammophon) or the irreplaceable Horowitz (RCA) with a quite different approach.

March-April 2003, Olivier Erouart

![]()

![]()

"Already published in 2000, this disc devoted to the two Rachmaninov sonatas by the pianist Lydia Jardon appears on the new AR RE-SE label, under which she now records. Its publication attracted attention at the time (Le Monde de la musique No. 244) because of the soloist's ability to place herself in an expressive perspective made up of commitment, power and flamboyance. These qualities did justice to pages of a difficulty of execution reserved for the digital prowess of Vladimir Horowitz or Rachmaninov himself. Indeed, the Russian composer remodelled his Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor in 1942 on the advice of the illustrious performer, thus achieving a synthesis between the complex original version of 1913 and the clearer one of 1931 chosen here by Lydia Jardon. In this page, as in Opus 28 with its paroxysmal outbursts, she demonstrates a capacity to crystallise opposites. Previously, Marie-Catherine Girod had shown in the Sonata No. 2 (in its original version) the intensity of a playing subjected to the realities of the construction. Today, Jardon takes these voluble pieces in hand to keep only the marrow. She can compare herself to the best interpreters: Horowitz, Fiorentino, Askhenazy, Ogdon, Wild, Kocsis (for Opus 36), Berezovsky (for Opus 28), Kun-Woo Paik or Weissenberg for the two sonatas.

February 2003, Michel Le Naour

![]()

"Winner of the Milosz Magin competition, Lydia Jardon has not taken the easy way out with this programme, which is usually almost exclusively reserved for men. The time is ripe for parity and it is particularly pleasant to note that the lyricism of these "symphonic" pages does not only belong to the stars, are they called Horowitz, Collard, Ashkenazy, Ogdon, Van Cliburn? For Lydia Jardon has moreover things to tell us. First of all, she has a sense of duration in the breathing, which is hardly easy in the immense First Sonata! She knows where the ultimate progression of the musical phrase leads and she gives it full resonance without breaking the chords. The piano is round, warm, the choice of a Kawai not being obvious when one knows the heaviness of the touch, but also the richness of the instrument's bass. From the First Sonata, the pianist draws the most diaphanous colours and her temperament allows her to carry the song with superb naturalness (Lento). The Second Sonata is perfectly mastered in its rhythm, which is both sharp and supple. Lydia Jardon takes the time to appropriate the score to bring out all the limpidity of the harmonies. The purely heroic aspect almost takes a back seat (Finale). One feels that the interpretation of the revised version is a choice that is justified here because it corresponds to the balance of the performance. The additions of the 1913 version would have added nothing to the understanding of a deeply animated and secret reading."

No 20, March 2000, Maxim Lawrence

"Pianist Lydia Jardon displays here a deep musicality and sensitivity, an enviable talent and a virtuoso technique. Her playing highlights many fascinating aspects of piano interpretation and technique in these two dauntingly difficult Sonatas: extremely sensitive treatment of tone, colour and dynamics, powerful projection of modes, supple tempi, a refusal to overdo it or hit the instrument, pearl-like transitions and, above all, a poetry, a rare ability to paint Rachmaninoff's music with a kind of 'brushstroke' that, for want of a better description, seems to recall the evocative paintings of Turner. All this is condensed into a canvas that is expressive and captivating. The rarely played First Sonata demands more than one listen, for it is a serious, densely textured work. Lydia Jardon plays this gloomy, dark piece ideally, bringing out its latent beauty with great effectiveness. Her approach to the more popular Second Sonata is similar (this is the 1931 version, revised by Rachmaninov) (...) The beautiful playing is very satisfying (...) Made by Lydia Jardon in 1999 at the Théâtre de Poissy on a Kawai EX piano, this recording deserves special mention, not least because it offers both sonatas. I hope to have the opportunity to hear this remarkable pianist again.

American Record Guide, Mulbury