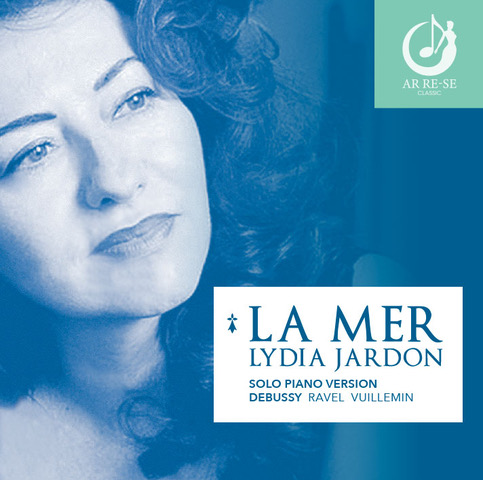

Product details

Claude Debussy

1.La Mer, piano version

2.L'Isle joyeuse

Maurice Ravel

3.A boat on the ocean

Louis Vuillemin

4.Soirs armoricains

AR RE-SE 2001-1

The Sea...

The four works in this programme invite us on a maritime voyage. A journey that begins at sea, in the centre of an unlimited expanse with La Mer (1903-1905), without any human presence. The Boat on the Ocean (1906), which follows, does not seem any more inhabited. It is only with the Soirs armoricains (1913-1918) that we come ashore populated by sailors. The journey ends on land with L'Isle joyeuse (1904), surrounded by ocean swells.

There is no shortage of literature on La Mer. But no commentator has studied it from a piano perspective, and for good reason. Yet the transcription for piano of this specifically orchestral work makes it a different work, and one that is entirely pianistic. It is indeed a transcription for the piano and not a reduction of the orchestral score, the word being too "reductive". Arrangements for piano four hands of orchestral works, often proposed by the composers themselves, had in the 19th century a very important function of diffusion of the works, inaccessible outside the concert halls. The arranger tried above all to "fit" between the four hands a maximum of the information intended for the orchestra, without trying to adapt perfectly to this single instrument. It is easy to see that "translating" La Mer for only two hands is a different matter. Lucien Garban (1877-1959), who took on this task in 1938, twenty years after Debussy's death, was a regular in this exercise. A fellow student of Ravel's at the Conservatoire and his faithful friend, he made his career as a corrector with Durand. The story does not say how Garban worked, but listening to the result one can imagine how familiar he was with Debussy's piano works. And in any case, in the early stages of the transcription process, he drew on the close relationship between Debussy's thoughts on composing for the orchestra and those of Debussy composing for the piano.

Debussy's writing for the piano is not orchestral, but it frequently evokes (and, so to speak, summons) this or that instrument: in many of his works, one hears guitar or mandolin, flute, horn, or brass fanfare. Conversely, reading and listening to Garban's transcription, one is reminded more than of orchestral works, of many works written by Debussy directly for the piano, before or after 1904. The work on tremolos, a writing trait so attached to the bowing characteristics of the strings or the rolls of the timpani, will be explored in the Poissons d'or or in Ce qu'a vu le vent d'Ouest. Writing in instrumental blocks is found in the chordal melodies that are a signature of Debussy's piano. Certain themes in La Mer, when played by two hands, no longer recall the orchestral version, but seem to refer directly to some piano piece: the theme of the first movement, after the introduction, seems to have come out of an etude; with its chained fifths, it would be somewhere between the etude Pour les quartes and Pour les sixtes! The theme of Jeux de vagues is a brother of the dance theme of Isle joyeuse, (the latter being only more pianistic!). One could multiply the examples that show to what extent this work becomes totally "for the piano". More difficult than the others, certainly, and sometimes even more difficult to play insofar as certain motifs written to facilitate the playing of a clarinet or a violin, end up on the keyboard as steep or perilous. In the end, the listener should not seek to hear the harps, the call of the eight cellos, the incredible transparency resulting from the division of the strings, the brass fanfares, it is a piano piece that he is listening to, even if the interpreter has had the possibility of listening to an orchestral version of the work with all the colours of the different timbres in order to nourish his (re-)creative imagination.

La Mer, not being written for the piano, did not seek to render by pianistic means all the movements of fluidity, flow, ebb, swell, that the liquid element can evoke. Ravel, on the contrary, in Une barque sur l'Océan continues the instrumental research already carried out in Jeux d'eau (1901). But whereas these games were then confined to a fountain or a basin, the composer has enlarged his space here. From the very beginning of the piece, the wave is born of large arpeggios in the left hand, rising and falling, made more turbulent by the ternary-binary uncertainty of the measure. Gradually these arpeggios will descend towards the low register and the piano's sound field will seem to cover the whole of the landscape, from the abyss to the firmament. Tremolo frizzes in the high register will be accompanied by even more extensive arpeggios, gusts covering seven octaves on the keyboard. The gusts will almost turn into a storm, until the fff, but the softness of the arpeggios and the resonance of the instrument will bring back the calm.

The human presence here is not at all certain, so frail does the boat seem in the face of the violence of the waves, and so deserted does the horizon seem, when everything is extinguished in the high pitch of the instrument. It is by continuing this voyage on the sea that this presence is affirmed, with the Soirs armoricains. In this suite of four pieces, the author has taken pains to multiply the tracks to allow the listener to follow. When one of the pieces is performed separately, he even asks that "the program indicate in parentheses: SOIRS ARMORICAINS, a precision that is essential to the understanding of the Music. Louis Vuillemin, composer, musicologist, critic, belongs to the generation of musicians born under the third republic, like Paul Ladmirault, Paul Le Flem, Rhené-Baton, Louis Aubert, who received their musical education in Paris, but whose creative vein is strongly anchored in their native Brittany. Ethnomusicological research was limited in Brittany at the time, and the Armorica recreated here is the one that the composer carries within him, with its load of visual and sonic impressions, which he transmits to us by means of notations at the beginning of each movement. For the first, Au large des clochers: "Serenity of a twilight... Undefined vibrations of the atmosphere... Sometimes distant and sometimes approached by the breeze, rumours coming from the earth... And, after scattered tinklings, the discord of the Angelus...". The piano must take up the challenge of giving life to this poetic world; it will do so with known means, but offered in an original way. Many long held notes or chords, often in the low register, which make the instrument resonate, and on which float popular modal songs with a Celtic flavour; frequent oppositions between different sound planes, required by indications such as "far away", "less far away", "less near", "sound". Bell effects already appear in this movement, but will be brought to a climax in Carillons dans la baie. The initial notation is more succinct: "Rhythms, songs, chimes. The composer excels here in making a few motifs revolve in the air, repeated as a litany, over which ring a few isolated bells that seem to be designed for the pleasure of the performer's thumbs, or ensembles of chimes, harmonies of bells that are strikingly true to sound. The last movement, Appareillage, with the same elements, brings us back to the world of men, with a tempo that is "lively, violent and obstinately rhythmic. Even more than in the first parts, the percussive character of the piano and its resonant possibilities are combined here, aided by the use of the pedal. But the expression is more intense, and the tension rises to the point of frenzy (a point shared with the end of La Mer and L'Isle joyeuse). It is through the relentless rhythm that this tension rises "always rigorously in the same movement". Even more than before, the repetition of the motifs and the volleys of bells produce a whirling movement, that of the human task endlessly restarted, suggested by the text proposed at the beginning: "Le Môle. Setting sun. High wind. Rearing up under the first embrace of the wave, a hundred heavy boats successively set off towards the open sea in an interminable symphony of noise, cries and songs. Iron, wood, canvas vibrate with the beings. Light. Movement. Strength. Joy. Life. »

L'Isle joyeuse, the end of our journey, is said to have been inspired to Debussy by Watteau's painting L'embarquement pour Cythère. However, we should not think of it as an island in the Mediterranean. It was in Jersey, in the middle of the ocean, where he had come to seek refuge from his love affair with Emma Bardac, that Debussy composed it. The island resounds with music and instruments: the flute at the beginning is undoubtedly that of a little shepherd who calls for rejoicing; the dance is present right away with a lively theme of communicative rhythm. The sea is present with the "undulating" accompaniment of the love theme that rises like an irrepressible wave. The second half of the work is an immense crescendo, with successive bursts of energy, which ends in exultation in the bubbling of the tremolos of chords, the same ones that concluded La Mer and which still bring together these two works that are already so close in terms of piano writing...

Anne Charlotte Remond

The press speaks about it

"In the last issue of Piano, le magazine (p. 77), we reduced the scope of the transcription for solo piano of La Mer. Lydia Jardon proves us wrong, recording this very version of the score (in its world premiere). Made in 1938 by Lucien Garban, a corrector at the Durand publishing house, this transcription is not totally irreproachable. Orchestral score in hand, certain details deserve to be clarified and refined; to mention just one, the cello singing at the beginning of the D flat passage of the first movement (bar 32), rendered in the left hand in a rudimentary manner, although it is perfectly executable. In any case, Lydia Jardon takes up the challenge. She brings this score to life with the greatest sensitivity, favouring a controlled and restrained expression rather than risking the richness of an abundant orchestra, among the most finely chiselled in the repertoire, with ten fingers. While the orchestra makes us feel the spray and the intoxication of the swell, Jardon's solo piano brings the sound of the waves from afar, just as the wind carries the iodized smell of the sea inland. There is no desire, therefore, to capsize the ensemble in a tour de force. In addition to Une barque sur l'océan and L'Isle joyeuse, both irrigated by the same poetic breath, the pianist adds to her programme Louis Vuillemin's Soirs armoricains, where the maritime perfumes still float. The project is impressive, as much for its originality and coherence as for the enthusiasm and poetry shown by Lydia Jardon.

Nicolas Southon

![]()

July-August 2002

"AR RE-SE ("Celles-là" in Breton) is a new label that offers performances recorded by women. In this first disc, Lydia Jardon has chosen "marine impressions" centred around Lucien Garban's transcription of Debussy's La Mer. If one expects here a literal translation of the orchestral score, one is mistaken. The three episodes refer to the author of the Preludes and especially the Images. It was in fact between these two notebooks for the piano that Debussy composed La Mer. Lucien Garban's writing thus achieves astonishing parallels with Reflets dans l'eau and Poissons d'or, which, notwithstanding the aquatic character of the subject, evolve in a quivering sensuality, a sparkling harmonic refinement. Lydia Jardon analyses in detail as much as she interprets these three sequences. The Steinway piano may seem harsh, especially in the upper register, but the result is strikingly clear. L'Isle joyeuse and Ravel's score show an equally penetrating analysis. Lydia Jardon is particularly attentive to the finest rhythmic changes. She exposes the exuberance unvarnished, perhaps also without concern for mystery or an overly 'prepared' sound (see Benedetti Michelangeli). The Soirs armoricains, whose pianist expresses the composer's text very well, breathe with a beautiful sense of space in a subtle play of dissonant harmonies. The almost hypnotic pulse she gives to them does justice to the falsely improvised spirit of these beautiful pages.

Summer 2002, Stéphane Friédérich.

![]()

"As early as 1905, Debussy delivered a transcription of La Mer for piano four hands. Three years later, Caplet adapted his friend's score for two pianos. These two reductions are relatively well known thanks to recordings, unlike the version Lucien Garban wrote in 1938. Given the abundance of the original, the adaptation for two hands is quite a challenge... which Garban takes up in a talented manner. No doubt the disorientation in familiar territory that this transcription provokes presupposes a few moments of adaptation, but Lydia Jardon - who signs a first recording - quickly convinces and captures the attention at the beginning of a programme as coherent as it is original, structured around the theme of the sea. For those already familiar with her superb Rachmaninov (Sonatas Nos. 1 and 2), Granados (Goyescas) and Chopin (Preludes), we can only recommend that they put their trust in the French pianist again. Une barque sur l'océan, carried away in a vast breath and without the shadow of a pause, and L'Isle joyeuse, sculpted, dreamlike to the point of being dreamlike (with the counterpart of an overall colour that one would like to see a little more scintillating at times), stand comparison with the great versions. However, apart from the transcription of La Mer, it is Vuillemin's Soirs armoricains (never before recorded) that are the main interest of this programme. A student of Fauré, Vuillemin (1879-1929) is to Brittany what Séverac was to Languedoc. Debussy said of the author of Cerdaña that his music 'smells good': the same could be said of the Soirs armoricains. The performer's ample and timbred but also very readable playing does justice to these rich and contrasting pages (splendid concluding Appareillage!)".

May 2002, Alain Cochard

![]()

![]()

"Organiser since 2001 of the Rencontres de musiciennes de l'île d'Ouessant, the Catalan-born pianist Lydia Jardon, whose performance of Granados' Goyescas (ILD - Le Monde de la musique, January 2001) was already well known, devotes this new recording to the theme of the sea. Of Debussy's La Mer, we know the reduction for piano four hands (the one, in particular, by the Duo Crommelynck-Claves), but Lydia Jardon, in a world premiere, reveals the transcription for solo piano of the orchestral score, made in 1938 by Lucien Garban (1877-1959), a corrector for the publisher Durand, close to Ravel and familiar with this high-risk exercise. The three pieces taken from Louis Vuillemin's Soirs armoricains, composed between 1913 and 1918, reveal a musician in the tradition of Paul Le Flem or Paul Ladmirault, a precursor of Olivier Messiaen through the play of timbres and sound aggregates ("Carillons dans la baie", "Appareillage"). The more traditional pages such as Une barque sur l'océan by Maurice Ravel and L'Isle joyeuse by Debussy complete the coherence of the whole. Lydia Jardon's superbly evocative playing not only lets us breathe in the sea spray, but also reads the texts that accompany Vuillemin's Soirs armoricains. This demanding disc, original in its choices, is all the more convincing because the sound recording is very natural.

May 2002, Michel Le Naour