Quartet No. 1 op. 51 in D

Quartet No. 2 op. 57

Sound engineer: Jean-Marc Laisné.

Recorded at the Saint-Marcel Lutheran Church in Paris on 2, 3, 4 and 5 October 2006.

Booklet: Ludovic Florin.

AR RE-SE 2006-3

Charles Koechlin's Quartets or the generous requirement

Charles Koechlin (1867-1950) was one of those men who seems to have had several lives in one, since, in addition to composition, he was interested in mathematics (after two years at the Polytechnique), astronomy, literature, architecture (he designed the plans of his secondary houses himself), photography and cinema. He was also a great walker who, from France to Turkey, via Spain and Greece, communed with the nature he travelled through. His scores reflect this open-mindedness: La Cité nouvelle for astronomy, The seven stars symphony for the cinema, Jean-Christophe after Romain Rolland, The Jungle Book, Les heures persanes, etc. Within each of them, one discovers many perfectly mastered musical styles. In the same opus, Koechlin can thus use Gregorian modality, tonal superposition and even atonalism, a way for him not to be dominated by any dogma. Yet he does not lose his soul, and a few bars are enough to recognise his sonic 'claw'. A highly independent spirit, it seems that he had to pay dearly for this courage in a country like France, which has a mania for classification and labelling. Indeed, Koechlin, one of the most important composers of the first half of the 20th century, is still too underestimated. That is why the present recording is of superior interest.

Even including Op. 122, two fugues composed in 1932, it may seem surprising that there are no more string quartets among the two hundred and twenty or so scores in his catalogue. Compared to his most prolific contemporaries (Milhaud, Shostakovich or Martinu, for example) Koechlin was not, however, content to write just one, like his master Fauré, or the likes of Debussy, Ravel and Roussel. From Fauré, Koechlin certainly retained the respect with which this formation, considered the highest in pure music since the dazzling achievements of Beethoven, should be approached. Yet he seemed ideally suited to maintain the genre for a long time. Among his colleagues, was he not one of the most learned, the one who was consulted when a thorny problem seemed to have no solution? This is what we are reminded of in his many didactic works, including the Traité d'harmonie (1924-25), the Traité d'orchestration (1954-59) and above all his Traité sur la Polyphonie modale (1931) for writing in four real voices for the quartet, his studies on the chorale (1929), the fugue (1934) and counterpoint (from 1926). The composer thus experimented with all possible instrumental combinations, from solo to large orchestra with soloists and choir. Nevertheless, his three quartets are representative of the stylistic evolution from his first to his second manner.

The dating of their composition is usually established as follows: First Quartet from 1911 to 1913; Second Quartet between 1915 and 1916; Third Quartet from 1917 to 1921. In reality, the sketches preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France show how much more extensive the conception of each of them was. For example, the first drafts of Quartet No. 1 bear the dates 22 May to 6 June 1902. Stamped by the SACEM on 10 July 1914, Koechlin was still devising 'variants (conforming to the edition)' on 28 February 1921. The composition of Opus 57 began in 1915, on 25 June to be precise, with sketches of the first movement. The scherzo was completed in September 1916. But the drafts of the finale are dated from 28 August 1909 to 1 August 1915. Koechlin then made a final revision of the quartet between 1 and 2 August 1921. Finally, the main ideas of the last quartet are spread out from 13 June 1913 to 18 August 1919, while the final chord was written on 15 August 1921. As we can see from this chronology, these quartets are not the result of a hasty rush. On the contrary, each note is weighed, thought out and rethought. All were finally revised in 1921, no doubt motivated by the hearing of his First Quartet op.51, which was premiered on 19 May 1921 in Paris by the Pascal Quartet.

By overshadowing the short Opuses 20, 32 and 34, Op.51 truly inaugurates the field of chamber music in the composer's catalogue. The dedication, 'To my master André Gédalge', goes beyond sincere gratitude and reveals the extent to which the writing is indebted to the teaching given at the Conservatoire's counterpoint and fugue class. Koechlin deploys in it a science of melodic line, of following the voices (with frequent crossings) which makes him, from his first attempt in this field, an ideal balance between technical mastery and musicality. Within a rather flexible sonata form, two themes are transformed, modulated, superimposed, in a very free manner far from any scholasticism. The bar lines are always present, but their perpetual capriciousness (6/4, 9/4, 12/4, 4 1/2/4, 3 1/2/4, etc.) tells us how much the music is too cramped in the straitjacket of the bar lines, which only asks to explode under the composer's pen. In the staggering of the cello's low open fifths to the celestial highs of the violinists, Koechlin's passion for the great mountain spaces he so loved to roam is perhaps reflected in a kind of unconscious and poetic transposition. The Scherzo that follows also has a very shifting metre. It is based on a melody close to a child's rhyme, as if the composer were trying to give back to the most learned procedures an original innocence. The colours of this diaphanous page are varied by a large number of different sonorities (pizzicatos, harmonics, extreme registers, tremolos, etc.) and by extraordinarily rapid changes of key.

The Andante quasi adagio is a nocturne with a perpetual movement of ineluctable eighth notes. A calm tension emanates from a rather romantic chromaticism wonderfully balanced by a dense writing with nuances never exceeding the mezzo piano. Its single melody runs continuously through the movement, passing from one instrument to another. The Finale seems less serious and takes the form of a pastiche of the First Vienna School. More particularly Haydn in the refrain with which this rondo begins, anticipating the neo-classical movement by several years. After the return of the refrain, the last verse brings a surprising modulation in C major where a very pure phrase unfolds in an almost gallant style. The conclusion becomes even clearer, calmer and ends not in D major (the original key) but in A major.

Never officially premiered, Op. 57 (which became the First Symphony, Op. 57 bis, after orchestration in 1927) is an apparently experimental work, with specific research being grafted onto each movement. In this perspective, the first movement would be a study of harmonies without a real theme, presented in the form of colour-changing arpeggios, a profoundly original thought in the musical panorama of its time. From the initial Adagio onwards, the tempo never ceases to slow down, in a staggering aesthetic of time close to the contemporary Persian Hours op.65 (1916-19). Far from being exotic, this temporality, which Koechlin surely perceived during his travels in the East, is an integral part of his language. Another time, chopped up this time, appears in the Scherzo which follows in a rhythmic study with ever-changing supports. It is a game in the strongest sense of the word, through the use, among other things, of an 11/8 time signature that was still quite unusual in 1916. After a more sedate central passage (in 6/8 time), the opening energy picks up again in a style already close to his future orchestral conception. The slow movement is a study in melodic variations on an ostinato of eighth notes. There is something unchanging about its simple writing, which is sometimes close to a chorale. The finale is the most developed movement of the three quartets, with no less than 335 bars (some of them in 15 beats!). Transcending the study, it is a masterly fugal demonstration without any of the overblown sentiment that is foreign to Koechlin's personality. With a marked taste for this form of writing, it reveals the admiration that this Parisian of Alsatian origin had for the music of the great masters of the other side of the Rhine, and in particular his true idolatry of Bach. The strings behave like a real orchestra with their double and triple strings, and incessant research into sound combinations. The first theme, frank and marked, which serves as the subject of the fugue, is soon superimposed on its counter-subject. This is followed by a substantial amount of imitative work. However, in certain places, Koechlin seems to deliberately disrupt a mechanism that seemed perhaps too well-oiled. And this within a more or less latent polytonality that is most successful. Elsewhere, he gives a deliberately archaic aspect to the proceedings by means of sudden changes of key underlined by the cello's empty fifths. Suddenly, an Andante contrasts with its peaceful C major. It precedes the resumption of music dominated by 'organised disorder'. This chaotic climax, the real centre of the movement, is finally projected into a sudden illumination, in a flamboyant E major. Gradually, in waves, everything calms down to leave the listener in awe of this fifteen minutes of intense listening. This is because Koechlin made no concessions as regards the realisation of his artistic dreams, since his music is 'both developed and interior, these passages being for people who are not in a hurry and who are capable of following with attention and sympathy a fairly long evolution of feelings', as he himself emphasised in a letter of 20 December 1932.

It is impossible to conclude otherwise than with the Étude sur Charles Koechlin par lui-même (1939): 'Incidentally, [Koechlin] is incapable of writing by analysing what he writes, to the extent that he never asks himself where the theme is... Sing, sing freely! Which is not to say that there is no order, nor that there are sometimes clearly defined motifs. But in reality, each of his works is a unique piece whose plan is determined by the lively evolution of themes and feelings, by life itself, - and which was never decided in advance, except sometimes in its broadest outline [...]. To achieve this, his music does not shy away from the demands of interpretation, technique and therefore listening. Perhaps too early, it is time for these important works to finally enter the repertoire alongside such intense successes as those of Bartók, Carter, Dutilleux or Ligeti.

Ludovic Florin

THE PRESS IS TALKING ABOUT IT!

![]()

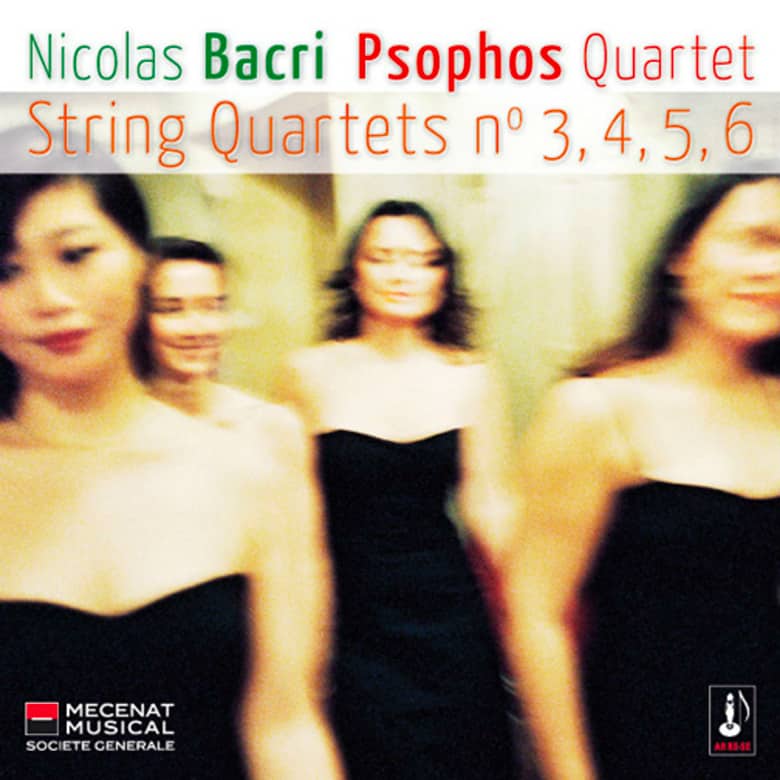

"Born in France in 1961, Nicolas Bacri has carved out his own path, carefully avoiding allegiance to any group of contemporary composers. Between tonality and atonality, his music is undeniably of our time but can be seen historically as part of Bartók's continuity. This recording covers a period of sixteen years from 1989 and unfolds the composer's rich sound palette and captivating rhythmic profiles, offering the newcomer a gateway to his musical world. These works pose a formidable technical challenge to the young French Psophos Quartet, especially the Sixth Quartet, where the music jumps from instrument to instrument with feverish anxiety. The Fifth Quartet, on the other hand, is mostly slow, with long, flowing lines in the second movement and the final Passacaglia resting on slight variations of calm dynamics. The Fifth Quartet takes Beethoven's Great Fugue as its point of departure, incorporating quotations from that model into its well-constructed framework, and the work's conclusion develops an aesthetic of staggered time quite different from the disturbing harmonies that run through the Third Quartet, written in memory of Zemlinsky. (...) The deep commitment of the Psophos Quartet performers, who throw themselves passionately into the frenetic passages, is unmistakable, as is their ability to create beauty in the static passages, where the solo instruments demonstrate their individual excellence. The recording is crisp with great precision of texture and balance."

The Strad, April 2008, David Denton

![]()

"Perhaps music is not there to satisfy man's curious thirst for certainty. Perhaps it is better to hope that music will always remain a transcendental language in the most extravagant sense. - Charles Ives. The publication in 2007 of the recording of Nicolas Bacri's third to sixth string quartets confirms his status as one of the leading figures in French contemporary music. Having begun his career in the serialism of the 1980s, Nicolas Bacri, while not quite having turned his back on it, no longer really communes with the cult of serialism: his music is clearly designed to arouse emotions and possesses an innate sense of flow and development, as well as a dramatic vein and an exalted atmosphere. At no time when listening to it does one get the impression that the composer is presenting you with the elements of which the music is made on the one hand and the result on the other. Bacri's music is the result of contact with a wide range of influences and creative impulses, but, as with Henri Dutilleux, the composer's voice is at the centre of his creation. Bacri has generated enthusiasm in a wide variety of musical genres, but his string quartet cycle, which is still unfinished since the seventh quartet was premiered in 2007, has earned him a particularly enthusiastic response from European critics. The French label Ar Ré-Sé has just released his quartets Nos 3-6, composed between 1985 and 2006, in a performance by the Psophos Quartet. This is a particularly happy correspondence between the performers and the composer: many quartets to which Bacri's music can be compared, at least superficially, are indeed in the Psophos repertoire (those of Berg, Bartok, Dutilleux, Webern, to name but a few). Founded in 1997, the Psophos Quartet is made up of young performers who bring all the strength, energy and passion of youth to Bacri's music. This recording will be a breath of fresh air for all those who love contemporary music in the 'twentieth century classical' style but avoid excessive abstraction and aerodynamics or, on the contrary, mawkish minimalism. Fans of string quartets will delight in the fireworks unleashed by the Psophos Quartet in this exhilarating and intellectually satisfying disc."

All Music Guide, April 2007, David N. Lewis

![]()

"With this delivery of four quartets by Bacri, the third completed in 1986, the sixth in 2006, we can hope that the seventh, commissioned at the last Bordeaux Competition, will soon find its way onto the record. (...) Bathed in a broad tonality, the discourse constantly circulates in the space between torment and bitterness, without ever settling on one of these poles. From this back and forth comes its eloquence, worthy of the post-Romantic universe of Transfigured Night or Webern's Langsamer Satz (listen to the opening bars of Quartet No. 5). In these masterly pages offered to his favourite genre, the quartet, Bacri has found the right balance between the preservation of his language and the necessary development of ideas, which has sometimes been lacking. The success is due to the abundance of melodic and harmonic discoveries, as much as to the continuity of thought that never weighs down the silhouette of the quartets. In the Prologo of the fourth, a moving harmony gives rise to a descending motif. The development superimposes them: the leitmotif is exposed to the changing radiance of the chords until the theme of Beethoven's Great Fugue appears, the backbone of this tribute. Familiar with Bacri's music, the Psophos excel in his sonorous mists or plaintive themes as well as in the fury that electrifies these pages brimming with imagination."

Diapason, January 2008, Nicolas Baron