Quartet No. 1 op. 51 in D

Quartet No. 2 op. 57

Sound engineer: Jean-Marc Laisné.

Recorded at the Saint-Marcel Lutheran Church in Paris on 2, 3, 4 and 5 October 2006.

Booklet: Ludovic Florin.

AR RE-SE 2006-3

Charles Koechlin's Quartets or the generous requirement

Charles Koechlin (1867-1950) was one of those men who seems to have had several lives in one, since, in addition to composition, he was interested in mathematics (after two years at the Polytechnique), astronomy, literature, architecture (he designed the plans of his secondary houses himself), photography and cinema. He was also a great walker who, from France to Turkey, via Spain and Greece, communed with the nature he travelled through. His scores reflect this open-mindedness: La Cité nouvelle for astronomy, The seven stars symphony for the cinema, Jean-Christophe after Romain Rolland, The Jungle Book, Les heures persanes, etc. Within each of them, one discovers many perfectly mastered musical styles. In the same opus, Koechlin can thus use Gregorian modality, tonal superposition and even atonalism, a way for him not to be dominated by any dogma. Yet he does not lose his soul, and a few bars are enough to recognise his sonic 'claw'. A highly independent spirit, it seems that he had to pay dearly for this courage in a country like France, which has a mania for classification and labelling. Indeed, Koechlin, one of the most important composers of the first half of the 20th century, is still too underestimated. That is why the present recording is of superior interest.

Even including Op. 122, two fugues composed in 1932, it may seem surprising that there are no more string quartets among the two hundred and twenty or so scores in his catalogue. Compared to his most prolific contemporaries (Milhaud, Shostakovich or Martinu, for example) Koechlin was not, however, content to write just one, like his master Fauré, or the likes of Debussy, Ravel and Roussel. From Fauré, Koechlin certainly retained the respect with which this formation, considered the highest in pure music since the dazzling achievements of Beethoven, should be approached. Yet he seemed ideally suited to maintain the genre for a long time. Among his colleagues, was he not one of the most learned, the one who was consulted when a thorny problem seemed to have no solution? This is what we are reminded of in his many didactic works, including the Traité d'harmonie (1924-25), the Traité d'orchestration (1954-59) and above all his Traité sur la Polyphonie modale (1931) for writing in four real voices for the quartet, his studies on the chorale (1929), the fugue (1934) and counterpoint (from 1926). The composer thus experimented with all possible instrumental combinations, from solo to large orchestra with soloists and choir. Nevertheless, his three quartets are representative of the stylistic evolution from his first to his second manner.

The dating of their composition is usually established as follows: First Quartet from 1911 to 1913; Second Quartet between 1915 and 1916; Third Quartet from 1917 to 1921. In reality, the sketches preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France show how much more extensive the conception of each of them was. For example, the first drafts of Quartet No. 1 bear the dates 22 May to 6 June 1902. Stamped by the SACEM on 10 July 1914, Koechlin was still devising 'variants (conforming to the edition)' on 28 February 1921. The composition of Opus 57 began in 1915, on 25 June to be precise, with sketches of the first movement. The scherzo was completed in September 1916. But the drafts of the finale are dated from 28 August 1909 to 1 August 1915. Koechlin then made a final revision of the quartet between 1 and 2 August 1921. Finally, the main ideas of the last quartet are spread out from 13 June 1913 to 18 August 1919, while the final chord was written on 15 August 1921. As we can see from this chronology, these quartets are not the result of a hasty rush. On the contrary, each note is weighed, thought out and rethought. All were finally revised in 1921, no doubt motivated by the hearing of his First Quartet op.51, which was premiered on 19 May 1921 in Paris by the Pascal Quartet.

By overshadowing the short Opuses 20, 32 and 34, Op.51 truly inaugurates the field of chamber music in the composer's catalogue. The dedication, 'To my master André Gédalge', goes beyond sincere gratitude and reveals the extent to which the writing is indebted to the teaching given at the Conservatoire's counterpoint and fugue class. Koechlin deploys in it a science of melodic line, of following the voices (with frequent crossings) which makes him, from his first attempt in this field, an ideal balance between technical mastery and musicality. Within a rather flexible sonata form, two themes are transformed, modulated, superimposed, in a very free manner far from any scholasticism. The bar lines are always present, but their perpetual capriciousness (6/4, 9/4, 12/4, 4 1/2/4, 3 1/2/4, etc.) tells us how much the music is too cramped in the straitjacket of the bar lines, which only asks to explode under the composer's pen. In the staggering of the cello's low open fifths to the celestial highs of the violinists, Koechlin's passion for the great mountain spaces he so loved to roam is perhaps reflected in a kind of unconscious and poetic transposition. The Scherzo that follows also has a very shifting metre. It is based on a melody close to a child's rhyme, as if the composer were trying to give back to the most learned procedures an original innocence. The colours of this diaphanous page are varied by a large number of different sonorities (pizzicatos, harmonics, extreme registers, tremolos, etc.) and by extraordinarily rapid changes of key.

The Andante quasi adagio is a nocturne with a perpetual movement of ineluctable eighth notes. A calm tension emanates from a rather romantic chromaticism wonderfully balanced by a dense writing with nuances never exceeding the mezzo piano. Its single melody runs continuously through the movement, passing from one instrument to another. The Finale seems less serious and takes the form of a pastiche of the First Vienna School. More particularly Haydn in the refrain with which this rondo begins, anticipating the neo-classical movement by several years. After the return of the refrain, the last verse brings a surprising modulation in C major where a very pure phrase unfolds in an almost gallant style. The conclusion becomes even clearer, calmer and ends not in D major (the original key) but in A major.

Never officially premiered, Op. 57 (which became the First Symphony, Op. 57 bis, after orchestration in 1927) is an apparently experimental work, with specific research being grafted onto each movement. In this perspective, the first movement would be a study of harmonies without a real theme, presented in the form of colour-changing arpeggios, a profoundly original thought in the musical panorama of its time. From the initial Adagio onwards, the tempo never ceases to slow down, in a staggering aesthetic of time close to the contemporary Persian Hours op.65 (1916-19). Far from being exotic, this temporality, which Koechlin surely perceived during his travels in the East, is an integral part of his language. Another time, chopped up this time, appears in the Scherzo which follows in a rhythmic study with ever-changing supports. It is a game in the strongest sense of the word, through the use, among other things, of an 11/8 time signature that was still quite unusual in 1916. After a more sedate central passage (in 6/8 time), the opening energy picks up again in a style already close to his future orchestral conception. The slow movement is a study in melodic variations on an ostinato of eighth notes. There is something unchanging about its simple writing, which is sometimes close to a chorale. The finale is the most developed movement of the three quartets, with no less than 335 bars (some of them in 15 beats!). Transcending the study, it is a masterly fugal demonstration without any of the overblown sentiment that is foreign to Koechlin's personality. With a marked taste for this form of writing, it reveals the admiration that this Parisian of Alsatian origin had for the music of the great masters of the other side of the Rhine, and in particular his true idolatry of Bach. The strings behave like a real orchestra with their double and triple strings, and incessant research into sound combinations. The first theme, frank and marked, which serves as the subject of the fugue, is soon superimposed on its counter-subject. This is followed by a substantial amount of imitative work. However, in certain places, Koechlin seems to deliberately disrupt a mechanism that seemed perhaps too well-oiled. And this within a more or less latent polytonality that is most successful. Elsewhere, he gives a deliberately archaic aspect to the proceedings by means of sudden changes of key underlined by the cello's empty fifths. Suddenly, an Andante contrasts with its peaceful C major. It precedes the resumption of music dominated by 'organised disorder'. This chaotic climax, the real centre of the movement, is finally projected into a sudden illumination, in a flamboyant E major. Gradually, in waves, everything calms down to leave the listener in awe of this fifteen minutes of intense listening. This is because Koechlin made no concessions as regards the realisation of his artistic dreams, since his music is 'both developed and interior, these passages being for people who are not in a hurry and who are capable of following with attention and sympathy a fairly long evolution of feelings', as he himself emphasised in a letter of 20 December 1932.

It is impossible to conclude otherwise than with the Étude sur Charles Koechlin par lui-même (1939): 'Incidentally, [Koechlin] is incapable of writing by analysing what he writes, to the extent that he never asks himself where the theme is... Sing, sing freely! Which is not to say that there is no order, nor that there are sometimes clearly defined motifs. But in reality, each of his works is a unique piece whose plan is determined by the lively evolution of themes and feelings, by life itself, - and which was never decided in advance, except sometimes in its broadest outline [...]. To achieve this, his music does not shy away from the demands of interpretation, technique and therefore listening. Perhaps too early, it is time for these important works to finally enter the repertoire alongside such intense successes as those of Bartók, Carter, Dutilleux or Ligeti.

Ludovic Florin

The press is talking about it!

![]()

"Here is a recording that is truly worth discovering, both for the extraordinary quartets of the composer and all-rounder Charles Koechlin (1867-1950) and for the Ardeo Quartet, recently formed by four young musicians who met in the string quartet class at the Paris Conservatoire and named after a Latin word meaning 'to be consumed by passion'. Difficult to characterise, Koechlin's remarkable music in these quartets is often polytonal and modal, but with a sense of melody that the composer manipulates in different ways, often taking the form of large fugal structures reminiscent of Bach. Quartet No. 1 is full of brilliant coups de théâtre. The monumental Quartet No. 2, which ends with an extraordinary last movement of 17 minutes, is contrapuntally rich and reveals vast and pure harmonic perspectives. What is surprising is not so much the fact that a young French quartet has chosen to record Koechlin as the overall mastery with which this performance is conducted. The young women burst into complicit joy in the final, Haydn-like movement of Op. 51, before indulging with pleading voluptuousness in the deconstruction of the sprawling aesthetic of the first movement of Op. 57. The recording seduces with its combination of clarity and warmth. Ludovic Florin's booklet explores Koechlin's work with relentless philosophical precision and musical detail."

Strings Magazine, February 2008, L. V.

![]()

![]()

"Navigating through Charles Koechlin's vast catalogue (over 250 works) proves daunting. Even the Grove is reluctant to give a complete list, although it does mention the three string quartets. The first two date from 1913 and 1916 and represent a valuable contribution to the composer's quietly but surely growing discography. Koechlin's natural musical environment is the orchestra, and he later orchestrated his Second Quartet, to which he gave the title First Symphony. In its original form, as in the First Quartet, it reveals the French roots of his music, with distant echoes of César Franck but also the Beethovenian tradition supported in French music by Vincent d'Indy. There is even more in these two works that distinguishes this composer, one of the most original and little-known of the first half of the 20th century, and the Ardeo Quartet's interpretations, which are highly flexible and admirably nuanced, deserve the widest possible distribution.

The Guardian, 23 November 2007, Andrew Clements

![]()

![]()

"In a world premiere, the Ar Ré-Sé label is releasing a recording of two string quartets by Koechlin, one of the greatest French composers of the 20th century. A young French string quartet, Ardeo was formed at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris in the string quartet class of M. Hentz and D. Hovora.

Fnac's opinion, Attention Talent

![]()

![]()

"The Ardeo Quartet has already won numerous prizes, from the Polignac Foundation to those awarded by the cities of Moscow (2004) and Bordeaux (2005), and has received regular or occasional instruction from members of the Fine Arts Quartet, the Hagen Quartet and the Talich Quartet (among others). We were therefore eager to hear the four Frenchwomen, especially in a programme that defends French music: Charles Koechlin's Quartets No. 1 and No. 2. Trained as a scientist and author of numerous dialectical works - Traité d'harmonie (1924-25), Traité d'orchestration (1954-59), Traité sur la polyphonie modale (1931) - it is not surprising to see the creator of the Heures persanes devote three opuses to a formation associated with musical quintessence. These were revised until 1921, in the enthusiasm of the premiere of the first (19 May) and the final touch to the last (15 August). The drafts of Quartet No.1 Op.51 bear the dates 22 May to 6 June 1902, but the actual composition takes place between 1911 and 1913. In addition to a rather long gestation period, Kœchlin conceived further variants (in accordance with the edition), until 28 February 1921. Dedicated to André Gédalge, a pupil of Massenet who became professor of counterpoint and fugue at the Paris Conservatoire, the work, if we exclude a few earlier pieces, represents the composer's true entry into the world of chamber music. This essay already shows a remarkable balance between musicality and technical mastery, country and sacred moods (Allegro moderato), knowledge and innocence (Scherzo), innovation and pastiche (Finale). The Quartet No.2 Op.57, which became the 1st Symphony Op.57bis after the 1927 orchestration, was never officially premiered and remains archived as an experimental work. Certain avenues of research can be identified: study of harmonies without a real theme (Adagio), unusual meter for the time (Scherzo), unbalanced movement length (seventeen minutes for the Finale), etc. There is a beautiful osmosis between the performers and the music, both developed and interior, of the composer - as he himself defined it in 1932. Their art of creating languid climates is based on a remarkable mastery of delicacy and nuance, the source of chiselled passages of great purity. The more rhythmic passages contain a never-wild joy, although they seem more bouncy than really danceable. This recording is particularly worthy of praise. »

Anaclase.com, October 2007, Laurent Bergnach

![]()

"The Ardeo Quartet magnifies KoechlinThis is a young ensemble that is making a lot of noise. Devoted to Koechlin's first two quartets, their new recording has been unanimously acclaimed by the critics. But the Ardeo Quartet, formed at the CNSMDP and supported by Mécénat musical Société générale, had already attracted attention in the past, obtaining in particular, in 2005, the 1st prize of the Fédération nationale des associations de parents d'élèves des conservatoires et écoles de musique, danse et art dramatique (Fnapec) and the press prize at the Bordeaux International String Quartet Competition. The ensemble has performed at major festivals and will play at the Septembre musical de l'Orne on 29 September.

Le Nouveau Musicien, N° 29, September 2007

![]()

![]()

"It is not surprising that a master of counterpoint such as Koechlin should have found from the outset the balance between the voices that is so essential to a harmonious dialogue between the partners in a genre that is reputed to be difficult (the string quartet). His first attempt in this field is in any case a master stroke: the dedication to his master André Gédalge (a true "French Taneïev" now scandalously forgotten) places this magnificent score under the sign of counterpoint and, in particular, of the imitation dear to Bach, a star in the musical firmament of our musician. The pastoral feeling tinged with modality alternates with clear melodies that have all the innocence of nursery rhymes sung by children in a large garden under the summer sun, and Dad Haydn himself seems to have taken the mischievous finale (a witty pastiche of the first Vienna School) to the baptismal font. Quartet No. 2 goes even further. Apart from Florent Schmitt's prodigious quartet, it is certainly the most monumental French quartet of its time. Its content goes far beyond the framework of the quartet, which explains why the composer orchestrated it as his first symphony. The solid tonal foundation does not prevent Koechlin from experimenting in a more daring way around 1915: "abstract" themes in arpeggio form (first movement, which is far from being "athematic" as the notice oddly suggests), slowing down in stages, tending towards a static immobility characteristic of the composer, a complex rhythmic study (Scherzo), and a highly personal solution to the oft-raised problem of synthesising fugue and sonata allegro. Polytonality and modality further expand the expressive possibilities and lead to a serene and luminous conclusion. Supported by the Ar Ré-Sé label (see the section "The makers of the disc", p. 24), the performers defend with great conviction these masterly pages, worthy of being included alongside the masterpieces of the genre such as Malipiero's quartets or those of Honegger at the time. Their perfect synchronisation and precision of attack allow one to savour the elegant curves of the dense modal polyphony that is Koechlin's signature. And a few fleeting inaccuracies are quickly forgotten in the face of the fervour and care with which the Ardeo build up the dynamic progressions, as in the middle part of the finale of No. 2. Such a well-considered approach will undoubtedly help to anchor these essential pages of French music in the current repertoire.

Classica-Repertoire, July-August 2007, Michel Fleury

![]()

"The years 1911-1921 were for Charles Koechlin those in which chamber music predominated.

From the First String Quartet, completed in 1913, to the First Quintet with Piano and Strings of 1921, the composer left his mark on established forms with his fundamentally independent personality. The study "Koechlin par lui-même", published in 1981 by La Revue musicale, describes the process by which Koechlin approached chamber music and, in particular, the string quartet: "Sing, sing freely! This does not mean that there is no order, nor that there are sometimes clearly defined motifs. But in reality, each of these works is a single piece whose plan is determined by the lively evolution of themes and feelings, by their very life.

It is necessary to remember this musician's view of himself in order to better understand what might confuse us when listening to these two string quartets, composed for the first between 1911 and 1913 and for the second between 1915 and 1916, dates retained by the catalogue published in 1975, But the text presenting this CD rectifies this, telling us that the first drafts of Opus 51 are dated from 22 May to 6 June 1902 (this text by Ludovic Florin is most complete, and is an important contribution to our knowledge of Koechlin's work).

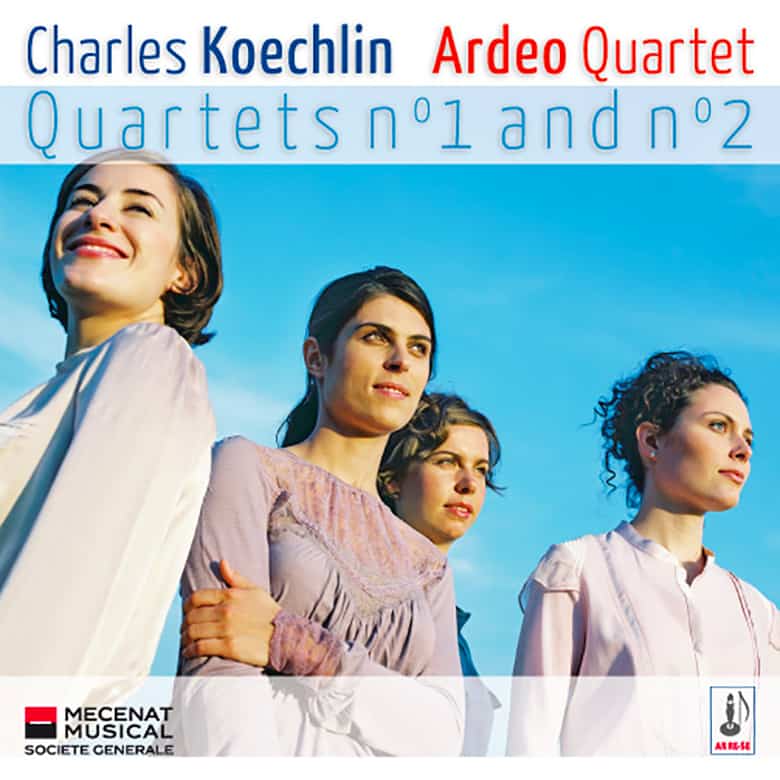

The performance of the Ardeo Quartet, formed in 2004 and composed of Carole Petitdemange and Olivia Hughes (violins), Caroline Donin (viola) and Joëlle Martinez (cello), is totally satisfactory for the cohesion of the four instruments and the spirit that animates the young performers. The time has finally come for Charles Koechlin's work to take its rightful place!

Le Monde de la musique, May 2006, Jean Roy

![]()

![]()

CD produced with the support of Mécenat Musical Société Générale