Productdetails

Quartet n°1

1.Polyphony

2.Monody

3.Déchant

4.Hymn

Quartet No. 2

1.Sagittarius

2.Mood

3.Alborada

4.Faran-Ngô

Quartet No. 3

1.Sorgin-Ngô

A world without shadows

The essence of the quartet, which has been present in every work since the genre began, is to create a dialogue between its actors. I speak, you contradict me, we listen to you and then retort; we speak at the same time, I remain silent, you listen to me, and so on. It is hard to see in what other century than the Enlightenment this conversation in music could have been born. One might think, some two and a half centuries after its birth, that its survival is a miracle.

Perhaps: but this miracle is.

Unchanged, both in nomenclature and in the attraction that, since its birth in Central Europe around 1770, it has exerted on composers - uniting them like few other forms inherited from the past, at the end of a twentieth century that saw the disappearance of any idea that the musical language was a common home - also uniting its performers under the same banner of "one for all, all for one", such is the string quartet today as it was yesterday. One would look in vain for another instrumental genre with such a constant quality of repertoire since its birth. Better still: judging by the number of string quartets still being composed, nothing seems to be able to stop its movement, or even to slow it down: past the year 2000 and its high level of sonic luxuriance (instrumental and electronic), the classical and sober string quartet is still alive. And what's more, it lives well.

However - and this is undoubtedly not the least of the paradoxes of which this demanding genre is the emblem, nor the least of its attractions - it was, remains and will always be "the tool of a certain asceticism" (Pierre Boulez): that which, with maximum sobriety of means (four instruments of the same family, two of which are identical) puts the composer, naked, face to face with himself. Only one law reigns here, with which each creator is free to organize himself, but which he can ignore: it is that of "line to line" (counterpoint) which underlies this musical conversation that is always being reinvented. To seem to refuse it, as Elliot Carter does in one of his quartets, which he divides into two duets that he wants to be foreign to each other (Third Quartet, 1971), or as Maurice Ohana does, whose polyphonic world predates that of baroque and classical instrumental writing, is, in short, to propose a radical modality.

Whether he comes from it (Schönberg) or not (Debussy, Dutilleux), no composer today is unaware that in composing a string quartet he is following a path traced by Haydn and Beethoven. Let us be clear: not so much a path called tradition, but a path called the demand for invention. It would be beyond the scope of this introduction to detail the originality of the founding father, whose evolution is not below that of Beethoven. But let us not forget: Haydn created, invented, and at the same time questioned (as his opuses 50 to 64 testify) and reinvented again (op. 76). And as the Viennese proverb says, "all good things come in threes", the 20th century had not yet reached its halfway point when Bartok's name was added to this list. Even a composer as resistant to the German musical heritage as Maurice Ohana did not deny the importance of this 'backbone' of the string quartet.

Here, everything is played out in full light. The quartet "exposes the weaknesses of thought as well as of realisation, magnifies the invention at the same time as it purifies it" (Pierre Boulez). Nothing escapes the listener; nothing in a quartet distracts, coats or embellishes the idea, nothing distracts the ear or allows the emotion to take a side road. Straight to the point: that is his law. This is the "game of truth", in which honest people - to name but three Beethoven, Bartok, Ohana - play without cheating or compromise. The fascinating sound object that is the quartet, without fat because it is all muscle, is obviously not without body: no one would dare claim today that Beethoven's last quartets, for example (some of which last the equivalent of an opera act) are too long. Take away a movement, a motif, a note, a simple bass pizzicato, and you will hear how necessary everything is. And this body of the quartet, which is of course anything but an abstraction - the reputation of "cerebral music" that clings to it should be put to rest once and for all - with Bartok and Webern, has learnt to accept itself with a sensuality that is one of the graces that the centuries of these two have bequeathed to music. A reservoir of new attitudes for string instruments, enhanced by new sounds (harmonics, slapped pizzicati, woodwinds, etc.), glissandi of all kinds, and playing with different scales, there is not a single post-war composer who has not made the most of it.

Without a commission, without any incentive other than the occasional one from a performer (for Maurice Ohana's sequences, it was the indefatigable Parrenin Quartet), Debussy, Boulez and Ohana wrote a string quartet at a pivotal moment for them. It must be acknowledged, however, that Ohana was the only one to do so again, and with pleasure (1), as a result of public commissions (the first from the Ministry of Culture, the second from Radio-France).

And yet, nothing predestined him for this. André Gide, who had heard him in Naples play 'remarkably' Bach, Scarlatti, Albenitz, Granados, Chopin's Fourth Ballad and Barcarolle (Diary, 27 December 1945), knew that he was listening to a pianist who had been a child prodigy (first public appearance at the age of 11, repertoire containing the complete Beethoven sonatas at the age of 18, etc.), and whose magnificent great recital at Pleyel in February 1936 was still remembered by many, including himself. Some (knowing him to be a composer as well) even drew parallels with Feruccio Busoni, an immense virtuoso and composer as well. A little later, Gide would compare this Spaniard of Andalusian origin with a British passport, who had chosen France, to Joseph Conrad, the Polish novelist (born in Ukraine) who had written all his work in English: a comparison which may seem artificial to those who do not know that one of the greatest novelists of the sea of all times, while the other built a work without meanders or losses, "all in marine movement chiselling away at the coast", according to Lucien Guerinel.

As a pianist, Ohana, whose piano writing is one of the most beautiful of his time, never denied his background in the written tradition: Chopin and Debussy. A catalogue that includes Preludes and Etudes is not born by chance. Moreover, in an attempt to surmise "the beautiful lesson of freedom contained in the blossoming of the trees", where the musician of the future could find material for renewal, as imagined by Debussy (2), Ohana claims: "the great lessons in music (...), I received them concretely from the sea and the wind, from the rain on the trees and the light...".

However, before giving himself completely to composition, he had to tear himself away from the practice of an all-consuming instrument (for which Ohana would later compose ceaselessly, always with a poetry that was tender, sensual and violent at the same time) and from the demands of a father who wanted his son to be an architect. The path is clear: after brief studies of writing at the Scola Cantorum with Jean-Yves Daniel-Lesur before a war in 1940 (which he fought in the British army), the course is completed in Rome with Alfredo Casella. A friendship was born. Following the example of his French predecessors (those of the "Groupe des Six", then the "Jeune France"), Ohana decided to come out of the woodwork and show his independence from all schools by creating the "Zodiaque" in 1947. Well beyond his ephemeral group (3) (not to say against it, since the notion of independence is so crucial and structuring for Ohana), this contributed to shaping "this character of absolute freedom, at the same time as of implacable artistic intransigence" (Francis Bayer), to which his opus 1, Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Mejias (1950), brilliantly bears witness.

From the beginning to the end of his catalogue, there are two constants - which are his preferred paths: the voice and the piano (as well as percussion, of which the piano is a part). The string quartets of contemporaries such as Ferneyhough, Wolfgang Rihm and Elliott Carter are matrixes, while Ohana's are more like consequences: the Sequences from Debussy's magical Tombeau (same use of thirds of tones within a work that is the quintessence of his art), the Second Quartet, with its mysterious second movement, grey as the light is between dog and wolf, with its great instrumental/vocal flatness seems to emerge from the sound world of Messe (1977), while continuing the work undertaken on the strings in Silenciaire (1969), as does the Third, which is much closer to the colours of La Célestine (1988) than to quartets born under other pens at the same period (Cage: Music fo four and Thirty Pieces; Ferneyhough: Third and Fourth Quartet).

Thus the lineaments of medieval plainsong writing, to which the movements of Séquences refer, the taste for keyboard percussion, whose mysteries he explored (4) (Second Caprice for piano, 1953; Silenciaire, 1969) and to which are linked all those vertical, homophonic sequences that bear Ohana's signature in each of the three quartets (Hymn in the Séquences, Sagittaire in the Second) ; as well as this movement, fundamental to his sound poetics, from flamenco to the Andalusian canto jondo from the depths from which he had to be extracted (and from which probably stems this attraction for writing in thirds of tones (5), which allows a melodic continuity that recalls the characteristic voice carriage), as well as these arrachés, These characteristic backstrokes (sff/pp) are the hallmark of his entire oeuvre, as is Africa, which is close to this pure southerner, and which is always on the prowl (Mood in the Second Quartet, or the injunction to the players in the middle of the Third Quartet to "think of Thelonious Monk"), not forgetting the Asia of Debussy's dreamlike pagodas (last page of Monodie). The performers of his string quartets know this well: Maurice Ohana does not so much write for quartet as he "tears" the quartet from its tradition, to annex it to his thoughts and melt it into his personal world, where the music will have come to him "from the light or from the contemplation of certain landscapes that I seek out because they seem to belong more to the creation of the world than to our civilised regions".

Stéphane Goldet

(1) According to Edith Canat de Chizy, composer and dedicatee of the Second String Quartet (cf. Edith Canat de Chizy and François Porcile: Maurice Ohana, Paris, Fayard, 2004). Among the 'non-Germans', however, there is a tendency to compose first quartets that are not particularly 'youthful' (Ohana was fifty when he began his first, Dutilleux and Fauré much older).

(2) La Revue Blanche, 1 June 1901 (reproduced in Monsieur Croche et autres écrits, p. 45).

(3) The "Zodiaque", conceived against the aesthetics of the "Jeune France" (whose options were, to tell the truth, quite diverse, and of which Ohana's former teacher, Jean-Yves Daniel-Lesur, was a member, as well as Olivier Messiaen) - "Jeune France" itself conceived to turn the page on the "Groupe des Six": and so on... The "Zodiaque", however, only had a short life of a few concerts between 1949 and 1950. In an era that was turning into ideological sectarianism, it was in fact a question of existing in the face of the "serial machine" successfully launched by René Leibowitz (notably with the "Messiaen class" at the Conservatoire).

(4) The most eloquent trace is found in the central movement of the five Sequences (Tympanum), which the composer unfortunately later disowned. For the one that was dearest to his heart and which, at the time, did not find a convincing performer ?

(5) Because of the nine commas that a tone contains, writing in thirds of tones is in fact more fluid and natural than writing in quarter tones, which was more frequently used from the 1960s onwards (Lutoslawski: Quartet, 1964). Independence, independence always...

The quotations are taken from Pierre Boulez's preface to the book "Quatuors du XXe siècle" (S. Goldet, Actes Sud-Papiers, 1986), as well as from the testimonies of relatives found on the composer's website (mauriceohana.com). The author would also like to thank Edith Canat de Chizy for the details she agreed to give him with the greatest of graces.

The press is talking about it!

"A British citizen born in Casablanca to Spanish parents, the Frenchman Maurice Ohana (1913-1992) is one of the most important composers of the second half of the 20th century, but is he really recognised for his true worth? Combining Debussy's refinement with the dirty harshness of Arab-Andalusian music, his writing found its fulfilment in the voice and the piano, of which this student of Lazare Lévy at the Paris Conservatoire was a virtuoso. But his writing, so poetic, also found a privileged expression in his three Quartets, too little known, and which we discover here magnificently defended by the four young women of the Psophos Quartet.

"Disks of the week", 18 November 2004, Christian Merlin and Bertrand Dicale

"Initially a prodigious pianist (he even accompanied La Argentina!), [Maurice Ohana] came to composition through the teaching of Daniel Lesur but also the patronage of Dutilleux. Receptive to dissonance to the end, he belongs to the individualist and modernist wing of the anti-serial reaction. (...) To this portrait of Ohana we can add the brand new recording of his three string quartets by the young ladies of the already renowned Psophos Quartet, collected and lyrical pieces that exacerbate a language that has remained classical.

Libération, 26 November 2004, Gérard Dupuy

"Maurice Ohana's work for string quartet is not so easy to get into: it is demanding and complex music that takes time to reveal its secrets and unfolds like so many cities whose beauties are born precisely from the shadows. There is, of course, a mystery to be unraveled, a mystery that neither the structure nor the language used by the composer can really illuminate. It is better, therefore, to let oneself be carried away and let the images arise in one's mind in order to savour his music. For there is much to be said for this: firstly, because this music plays precisely on the imagination, as if it were trying to construct an almost palpable world with sounds. Secondly, because it often unfolds like a slow tracking shot over a few motionless landscapes, animated only by the sudden flashes of a blinding sun. There is, of course, something cinematographic - a cinema almost without narration that returns to the essential: images and the art of editing - in this way of thinking about the unfolding of a work. The succession of shots, the cross-fades, the poetry of images that replace the real world, all this is found in Ohana, magnified today by the unvarnished playing of the Psophos Quartet.

Arte, December 2004, Mathias Heizmann

"Like the Three Musketeers, the Three Graces are in fact four, and they form the Psophos Quartet. These funny ladies offer us a recording that will make even the most reluctant listeners love contemporary music: "You don't like contemporary music? You haven't heard the Psophos Quartet in Maurice Ohana's quartets! It must be said that Maurice Ohana is an atypical composer, with a personal language that frees itself from any stylistic or aesthetic school, and in particular the German dodecaphonic school. Eminently poetic, Ohana favours rigorous and subtle writing - invoking plainsong in his First Quartet - with Mediterranean lyricism (and notably Andalusian and African in Quartets Nos. 2 and 3), focusing his work on timbre - hence the use of thirds of a tone and modern playing of string instruments (harmonics, woodwinds, slapped pizzicatos, etc.) Ohana then renewed the way of writing for quartet, adapting it to his language and freeing it from the traditional polyphonic rigour. In this recording, everything is there, and first of all a remarkable precision of ensemble and homogeneity of sound. Their energy is reflected in a very sure and nervous bow, ideal for "those characteristic backstrokes - sff-pp - which characterise Ohana's entire work", as indicated in the booklet, but from which emerges, even in the most abrupt cutting, a great beauty of sound, far from the scalpel-like interpretations too often encountered in this repertoire. As for the accuracy, even the thirds of a tone sound with perfect precision. The harmonic encounters occur without a shadow of hesitation. The four musicians play this music, which requires all the "modern" techniques of string instruments, with disconcerting ease and with a rare commitment and pleasure. Endowed with a plethoric expressive palette, a great variety of vibratos, a formidable sound but also much more intimate depending on the needs, these young women know how to do everything. With extraordinary authority, they render the structure of the quartets perfectly and the listener is never lost, even in music that is far from obvious. And it is this obviousness that carries us away. Each moment is inspired, placed in the context of the works, whose different movements are wonderfully unified. With an incredible subtlety, an intimidating technical perfection and tone, one is left, admiring, to listen to these works in religious contemplation, which is particularly rare, a fortiori in this repertoire, hoping for only one thing: that it lasts a long time. Felt, felt, experienced, perfectly rendered, all this is beautiful, because the Psophos Quartet never forgets the aesthetic aspect, too often neglected. Yes, it is modern, and it is beautiful! So our Quatre Grâces have pulled off a very nice coup: to be the reference for a very long time in these works, and to be in a very good position in the cenacle of young French quartets. Let's hope that the Psophos Quartet will confirm this in the future, this time in more "traditional" works of the repertoire - their first Mendelssohn recording (Zig-Zag Territoires) gives us hope.

Classica-Repertoire, February 2005, Antoine Mignon

" Discophage: the best recordings

The Psophos Quartet proves to have a breathtaking technical mastery, which allows them a constant sound beauty, even through the most modern playing techniques, from slapped pizzicato to thirds of a tone. And the recording proves to be impeccably pure and precise, restoring the four instruments perfectly individualised in space with their fleshy sonorities and phenomenal presence, in the most recollected moments as well as in the most brilliant. »

March 2005, Philippe van den Bosch

![]()

"To our knowledge, this is the only published recording of Maurice Ohana's three quartets. The first of them is entitled Cinq séquences (1963), but the Psophos have decided to remove the central Tympanum in accordance with the composer's preferences (this movement should appear on the version of the Danel Quartet planned for Timpani). Polyphony, Monody, Dechant, Hymn: the titles suggest the variety of techniques as much as the reference to medieval vocal music. This austere language with its angular contours, dry as a vine, is irrigated by the playing of the Psophos with a welcome sap (Monodie), setting the tears of Hymne on fire. Quartet No. 2 (1980) extends the ritual to Andalusian cante jondo and spiritual. An epidermic Sagittarius announces the cabalistic jolts of Alborada before the superb last movement, Faran-Ngô, known in its orchestral version as Crypt (1980). The Psophos affirm with equal conviction the telluric power of the Third Quartet, Sorgin-Ngô (1989), which treads the chalk and ochre of its Basque metrics. The young French quartet is eagerly awaited for this new release, and takes up this music with feverish meticulousness, combining driving energy and fullness of sound, iron bow and velvet hair.

Diapason, February 2005, Nicolas Baron

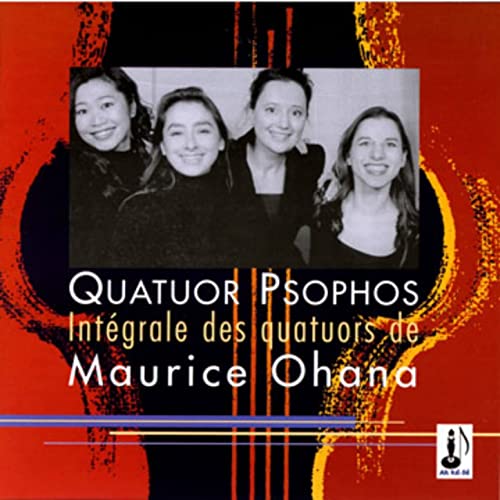

"The Psophos Quartet (in Greek "the sound event") was founded in 1997 at the National Conservatory of Lyon and has won numerous international competitions, including the First Grand Prize of the Bordeaux International String Quartet Competition in September 2001. Since then, he has been invited to perform on the most important stages and international festivals (Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Wigmore Hall in London, Les Folles Journées in Nantes, Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels...) and shares his passion for chamber music with many French soloists (Jean-Claude Pennetier, Alain Meunier, Frank Braley...).

The Psophos Quartet's first CD recording, the complete quartets of Maurice Ohana, with which it won the Maurice Ohana Prize and the Mécénat Musical Société Générale Prize, clearly testifies to the curiosity and enterprising spirit of the all-female ensemble. There is nothing traditional in the universe of these three quartets, which radically turn their backs on the German heritage and the law of counterpoint to join the composer's personal world of sound; the refinement of timbres, the echo of the rhythms and instruments of Africa, which fascinates Ohana, and the extreme diversity of fluid or compact, homogeneous or fragmented textures nourish the lines of the quartet as they do those of his vocal music or his work for piano. Totally committed to the search for colours and specific textures, calling on a wide variety of playing modes and with a perfect mastery of the third-tone inflections that Ohana is particularly fond of, the Psophos Quartet tends here to become a veritable generator of sounds, shaping its sound object in continuous metamorphosis.

The titles of the four movements of the First Quartet refer to four types of writing - Polyphony, Monody, Dechant, and Hymn - which have their roots in a distantly evoked Middle Ages. The final Hymn uses the vertical and homophonic writing of the four desks, requiring, as in Messiaen's work, perfect synchronisation of gesture and energy within a quartet whose sound qualities and rich palette of timbres can be appreciated here. Stranger still and more mysterious in its musical itinerary, the Second Quartet diversifies the universe of each of its four movements - Sagittaire, Mood, Alborada, Faran-Ngô. In Sagittaire, there is a play of contrasts between the supple, 'smoothed' trajectory of the sound and the rough and tumble of certain more tormented surfaces. The deep pizzicatti of the low strings in Mood evoke the mysterious echo of skin percussion disrupting the calm of the large instrumental flat tones. Alborada is permeated by a luminous vibration radiating from the sound material, while Faran-Ngô seems to sum up, in its very 'uneven' course, the extreme diversity of the instrumental playing deployed throughout the score. Between languor and surge, murmur and clamour, the Third Sorgin-Ngô Quartet, written in a single piece, is nourished by contrasts. Episodes pulsating with an almost savage rhythmic pattern are followed by stretches of pure sound poetry, both tender and sensual. With energy and sound potential at the service of musical invention, the Psophos Quartet takes us on a journey into these mysterious faraway places, these dreamlike landscapes, with total artistic commitment to reach the essence of a poetic sound.

This superb recording, which completes Ohana's discography, coincides with the imminent release of a now essential monograph on the composer written by Edith Canat de Chizy and François Porcille, published by Fayard.

ResMusica.com, 7 January 2005, Michèle Tosi

"Maurice Ohana remains the most obscure and unknown of the great composers of the second half of the last century, so much so that in most countries his name is still unknown! And who knows that, among other things, he enriched the repertoire of the string quartet with three major works? These are undoubtedly his least known works, so that their first recording, more than twelve years after his death, is a real event. (...) If all her music is at odds with Germanic traditions, a rejection that she proudly claims, this rejection confronts her with the challenge of almost totally renouncing the polyphony that seems inseparable from the genre of the Quartet itself, along with the dialectical thinking made up of contrasts and thematic developments that is its consequence. This means that these pages stand apart from all the masterpieces of the genre, and concentrate on other elements of language: the monodic or at least heterophonic melos, the variety and richness of the rhythms, the extraordinary refinement of the harmony, and lastly, and perhaps above all, the timbre, the work on sound, which places Ohana right at the centre of the dominant trend of the young music's marching wing. The intimate essence of these works is the magic and enchantment of rituals, those of the Andalusian Cante jondo as well as those of Jazz, two major sources of inspiration for Maurice Ohana, who was also in search of the archetypal, even prehistoric origins of music. In other words, we are a long way from Haydn and Beethoven, and only slightly less far from Bartók, whose 'nocturnal' music still has echoes in the Five Sequences, although the composer's very personal universe and language are already fully apparent. The Second Quartet is the most intimate, the most secretive, no doubt, the most difficult to access, but it contains perhaps the most exciting sonic discoveries. The Third, finally, one of his last great works, is a grandiose achievement, the most extensive, though in one piece, more 'classical' perhaps, containing in particular a brief but extraordinary tribute to Thelonious Monk. Even if no one knows it yet (this CD will help) it is, quite simply, one of the supreme masterpieces of the genre, and not only in the twentieth century! (...) This product of a very small independent publisher, whose distribution we hope will not be too confidential (but it has found its way to our review!) constitutes an event of the utmost importance, thanks to which the opera La Célestine remains the last gaping hole in the Ohanian discography...".

Crescendo, February-March 2005, Harry Halbreich

" The demand and the freedom

We discovered them some time ago in Mendelssohn and, as it happens, the four young women of the Psophos Quartet made a big impression on us... Well, in a world of quartets that is, if not misogynistic, at least rather masculine, here is a confirmation that makes us very happy: Ayako Tanaka and her accomplices have had the wonderful idea of recording the complete quartets of Maurice Ohana, a sorcerer in a way, a dowser in a way... And not only do they offer what will be for many a superb discovery, they also remind us that the musician's credo has not lost an ounce of its relevance. More than ever, we must defend the freedom of musical language against all tyrannical aesthetics. The softest are not the least dangerous...

La Libre Essentielle, March 2005

"The fact that Maurice Ohana (1914-1992) wrote quartets, and moreover without any particular commission, may come as a surprise. The genre is in fact mainly linked to the German-Austrian musical tradition, which the composer distrusted. Ohana therefore used the quartet as an instrumental formation and as a writing technique to further develop certain aspects of his language and aesthetics.

The first dates from 1963 - contemporary, therefore, with the Tombeau de Claude Debussy. The work originally consisted of five parts, but Ohana removed the central section (Tympanum) and it is a pity that in this version the performers did not dare to reintroduce it. Each movement refers to medieval modes of writing (Polyphony-Monody-Desire-Hymn). The work makes abundant use of thirds of a tone, which gives it a rough, singular and archaic colour.

This typically Ohanian taste for non-classical musical traditions (i.e. not inspired by European art music) can be found in the Second Quartet (1980), which refers both to 'cante jondo' and to African music, in its early form and in the American form of gospel. The last Quartet, Sorgin-Ngô, in a long, firmly constructed 24-minute movement (1989) is contemporary with the opera La Célestine. Here, the search for complex rhythms, the play of sound masses, and everything that connotes harshness and mineral hardness dominate.

The interest of these releases, which give access to three masterpieces of the music of our time that have been too little known until now, cannot be underestimated. This CD is also the first commercial recording of the Psophos Quartet, an all-female group formed in 1997 and already very well known. For the four young instrumentalists, it is obviously a challenge to have started with these not really known and very demanding pages. The challenge was met. The instrumental qualities of the Psophos are extraordinary, both in terms of accuracy (especially in the thirds of a tone!) and in the variety of colours or the powerful play of rhythm and volume in the Third Quartet. The revelation of three masterpieces is thus doubled by that of a great string quartet. When will we hear more?

ClassicsToday France, Jacques Bonnaure

"Listeners unfamiliar with Maurice Ohana (1914-1992), a composer of varied heritage - a British national born in North Africa to Spanish parents, who studied in Rome and eventually settled in Paris - will benefit from Lindsay Koob's review of his choral works (in the September/October 2004 issue). As Koob points out, Ohana was unique: "an isolated phenomenon... a kind of one-man music movement, small (about 50 works) but important.

Fascinated by exotic and primitive music, Ohana set out to develop a kind of modern recreation of it using avant-garde techniques. The result is dense but vibrant, austere but sensual, impressionistic but abstract, oblique but striking, new but ancient. There are kinships with Bartok, with Berg, and most clearly with the ecstatic, visionary music of Messiaen and Dutilleux - but Ohana is wilder, rougher. Like the harsh landscapes it evokes, his music is never pretty but can be painfully beautiful. As Koob says, "It requires patience, concentration, and repeated listening.

To be honest, I never appreciated Ohana's music until now. It seemed too inaccessible and formless. To my surprise, however, I quickly entered the world of these quartets. The intricate textures and unusual string effects - pizzicati, out-of-sync glissandi and harmonies, jolting col legnos, microtonal clusters, psalmodic and florid recitatives, shifting ostinatos - appear as absolutely consubstantial to the musical argument rather than as superficial, flashy decoration. This music of rock-solid integrity has an "obviousness" and logic that, however unconventional, is obvious from the start. It simply burns with an expressive fervour that recalls the most intense moments of Bloch's music, such as his scintillating Second Sonata. The musicians of the Psophos Quartet play as if possessed; their vivid-silver intensity and superb concordance are beautifully rendered in Ar Ré-sé's holographic recording.

Sensitive souls beware! But those who like to think outside the box will find a rich reward here. I hope that the Psophos Quartet will continue to explore this kind of neglected repertoire. I would love to hear them in some of the fine quartets of Barraud, Nikiprowetsky and other modern composers in the French tradition.

American Record Guide, Lehman